The Milwaukee Public Museum holds the most comprehensive collection of Mexican Kickapoo material in the United States.

This is due to the fieldwork conducted by Ritzenthaler and Peterson in the 1950s and Felipe and Dolores Latorre in the 1960s and 1970s. The collection contains artifacts that represent daily life in the Mexican Kickapoo village as observed by the Latorres, and includes leatherwork, clothing, adornment, tools used for preparing food, basketry, hunting items, pipes, ceremonial items, musical instruments, toys and games. In addition, the Ritzenthaler/Peterson expedition took over 100 black and white photographs and shot 1100 feet of Kodachrome motion pictures. The ethnographic specimens combined with the photographic documentation of the community paints a unique visual story of the Mexican Kickapoo at a specific time and place.

Clothing

Traditionally, both men and women wore calico, a cotton fabric often covered with a small flowers or other print. This fabric is most commonly associated with pioneer women’s dresses and, in fact the style of the Mexican Kickapoo was described as having been inspired by the pioneer style of dress during the mid-1800s. For men, this consisted of a calico print long-sleeve shirt and sometimes a vest adorned with beads and silverwork. Women wore full skirts and long sleeve blouses, both cut from bold calico prints.

Women’s Calico Shirt (E62427)

Women’s Calico Shirt – Collar (E62428)

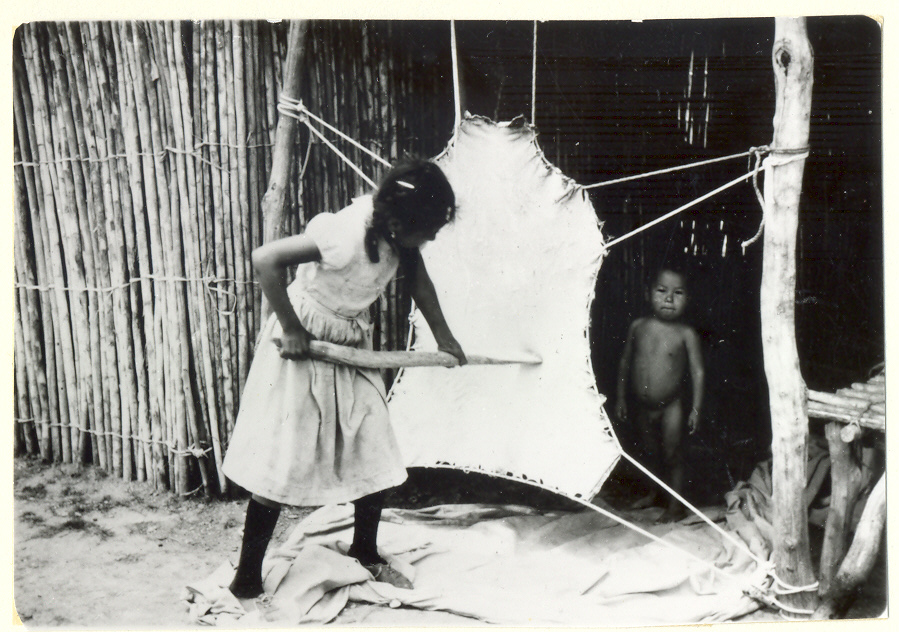

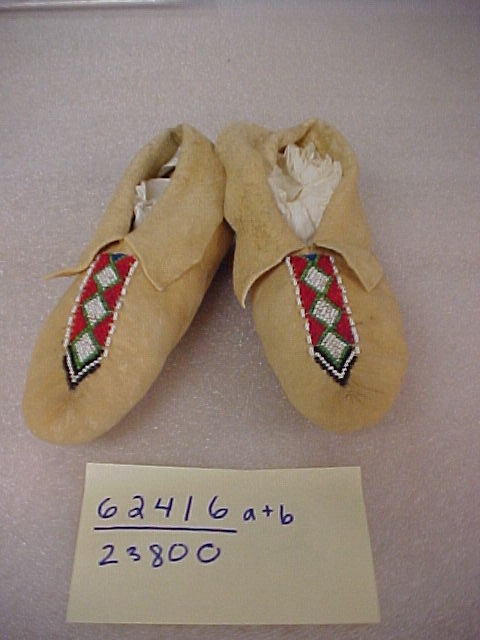

Also included in the traditional dress for men were buckskin breechcloths, leggings, and moccasins. Leather breech cloths and leggings are now reserved for ceremonies, but moccasins are still everyday wear. The Latorres noted that there were two types of moccasins: those made from a single piece and those made from two. Single-piece moccasins are the most popular, recognized by a distinctive cuff around the foot opening and the geometrically designed beadwork on the in-step. Two-piece moccasins have an extra piece of tough bovine leather sewn to the bottom for walking the rough mountain trails, and are never decorated with bead work.

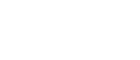

“Preparing Deer Skin”

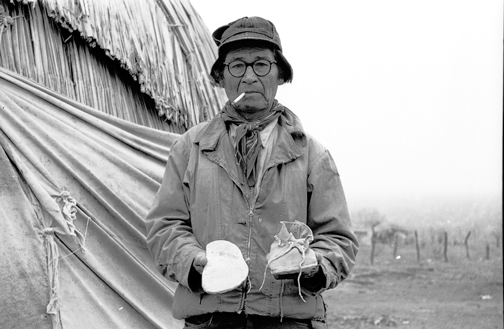

“Man Holding a Pair of Two-piece Moccasins”

Adornment

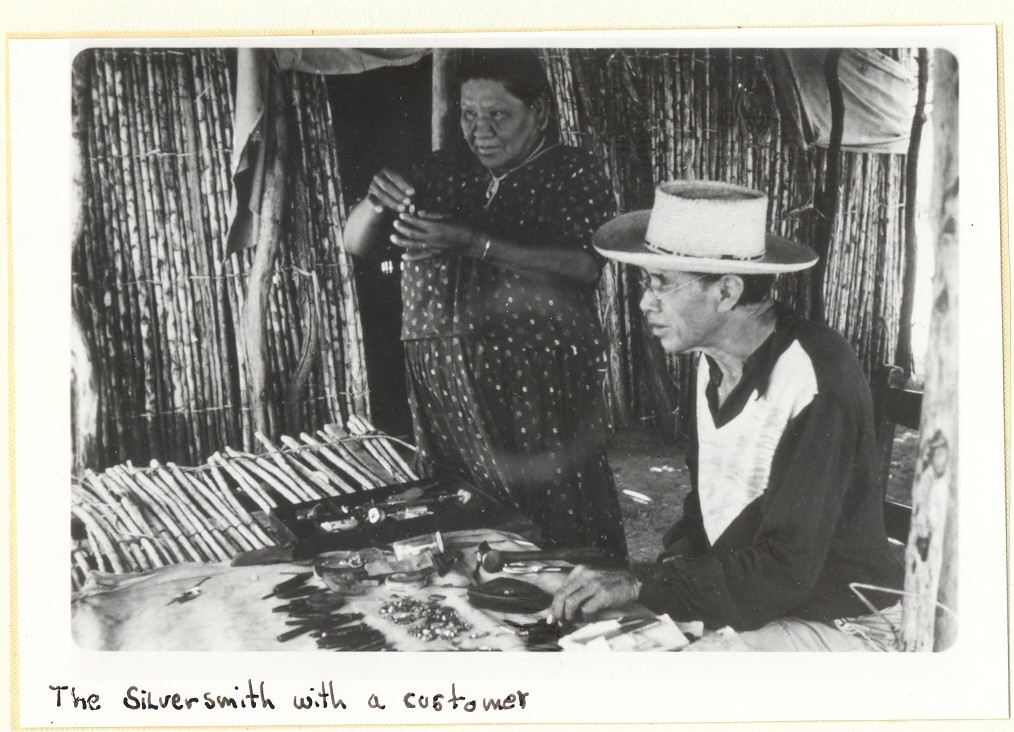

“The Silversmith with a Customer”

The German silverwork collected by the Latorres comprises the majority of Mexican Kickapoo items at the Milwaukee Public Museum. Brought to the Americas by the Spanish in the 16th century and adopted by the Navajo, German-silver is actually a composite of copper, nickel, and zinc. The name is due to the silver color of the items, and is often mistaken for silver. Both Mexican Kickapoo men and women adorned themselves with German-silver work including bracelets, brooches, buckles, buttons, hair combs, earrings, kerchief and queue rings, and finger rings. The silverwork worn today is limited to ceremonies for men, and women only wear the bracelets, rings and earrings. Items are often incised with geometric patterns and are sometimes inlaid with various stones and abalone shell from Mexico.

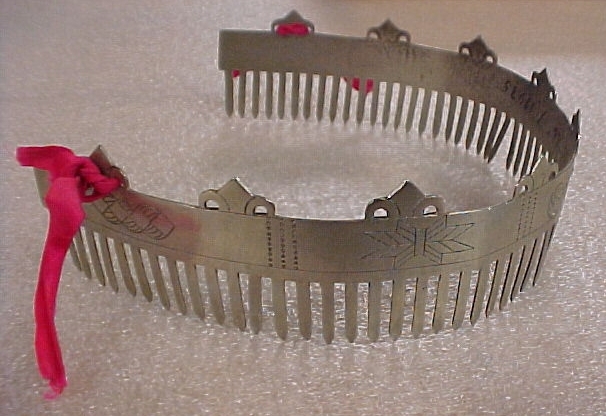

Hair Comb

E62463 Detail

E62463

Bracelets

E642441

E62442

E62443

E62449

Rings

E62471

E62472

E62478

E62494

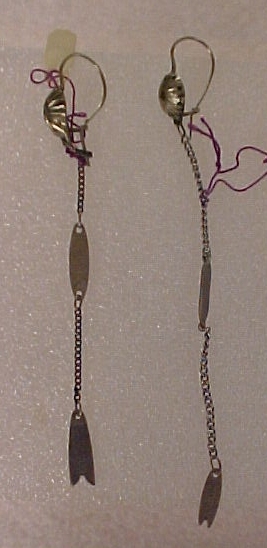

Earrings

E62582

E62586

E62587

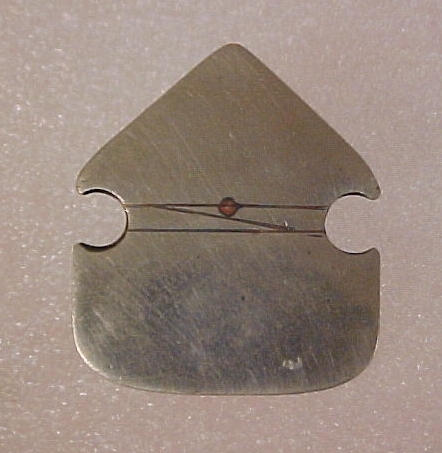

Buckles

E62501

E62506

E62509

Brooches

E62538

E62568 (1&2 of 8)

E62568 (3&4 of 8)

Daily Utilitarian Objects

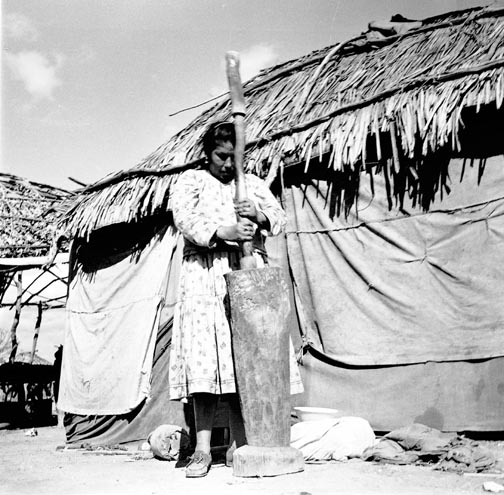

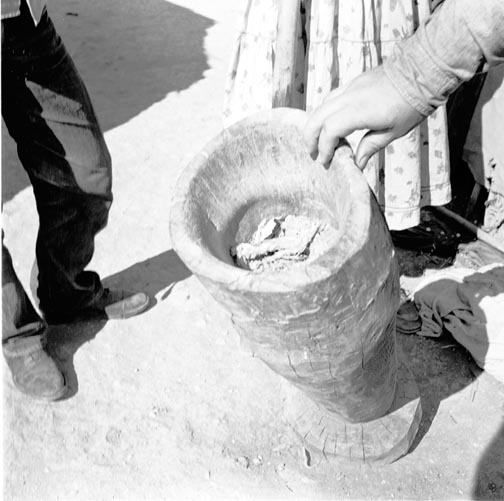

The Latorres noted that many of the traditional household items constructed of ceramic, wood, and stone were replaced by iron and enameled ware, however, the stone mano and metate and the mortar and pestle were still in use for food preparation. Both serve a similar grinding function but for different purposes. The mortar and pestle, used for rubbing items such as corn (maize) and jerky into a fine powder, is much larger and constructed of wood. The mano and metate is hand-held and made of Mexican volcanic rock. These are common items in other Mexican homes and throughout Latin America, and are useful for grinding maize, onion, peppers, garlic, and spices.

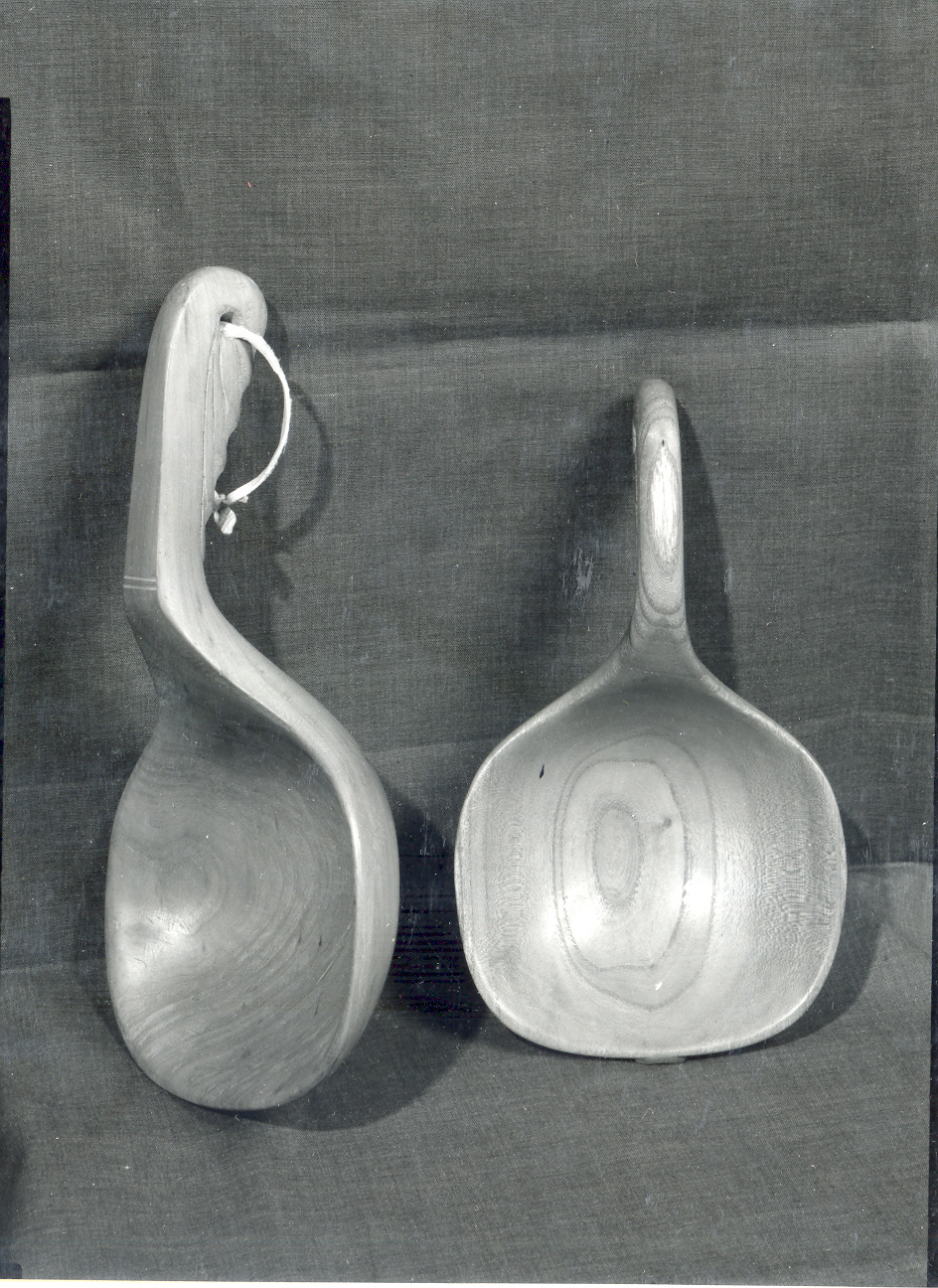

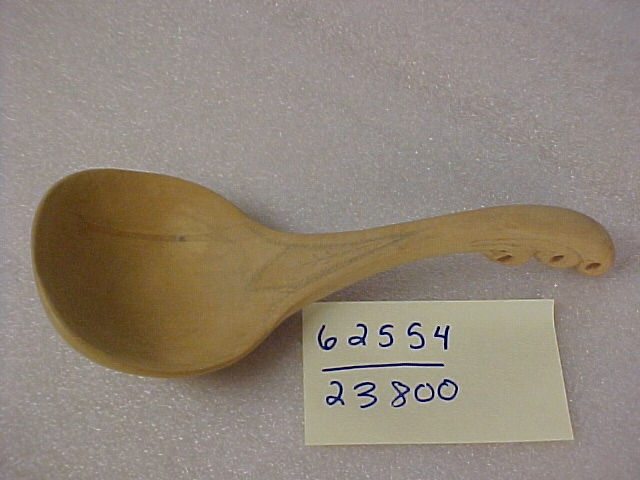

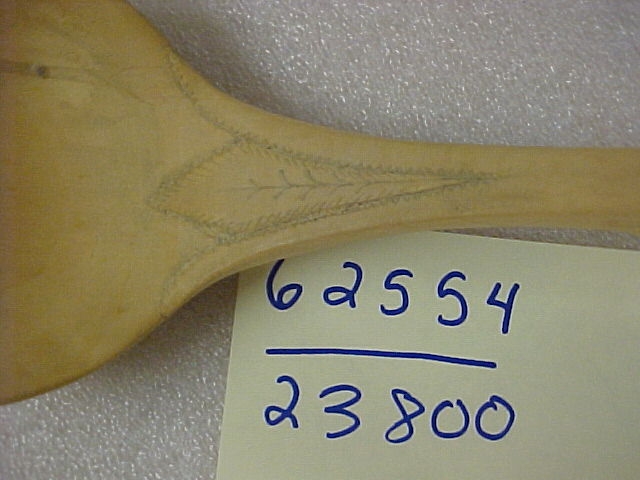

Ceramic pottery was replaced by brass kettles brought by the French. These are now reserved for ceremonial meals, and black ironware is more commonly used for food preparation. Iron tripods belay iron pots and kettles over house fires - perfect for frying bread, cooking soups, and preparing beans. Wooden bowls and ladles are used but only for ceremonial meals.

“Ironware : Tripod and Bucket”

“Woodworking”

“Wooden Ladles”

E62554

E62554 Detail

Basketry is one form of reed-woven work practiced by Mexican Kickapoo women. Traditionally, the woodland Indians of the Great Lakes region used birch bark for housing and baskets. As a result, Ritzenthaler and Peterson speculated that the practice of woven basketry was adopted from Mexican work in Coahuila; the Latorres, however, noted that there is no evidence of basketry in Coahuila. In response to the lack of birch bark, the Latorres speculated that the Mexican Kickapoo made do with what they had around them, specifically the sotol plant or “desert spoon.” The first baskets were plain, but when they became a popular trade item in the markets in Coahuila, colors were integrated into the weave work to appeal to the Mexican customers.

“Basket Weaving”

Baskets

E55850

E55851

E62393

E66886

E62396

E62397

E62398

E62404

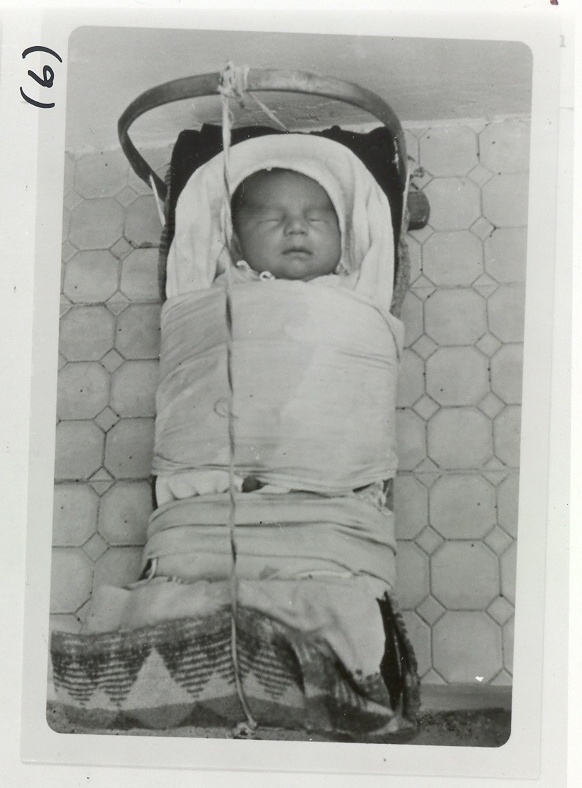

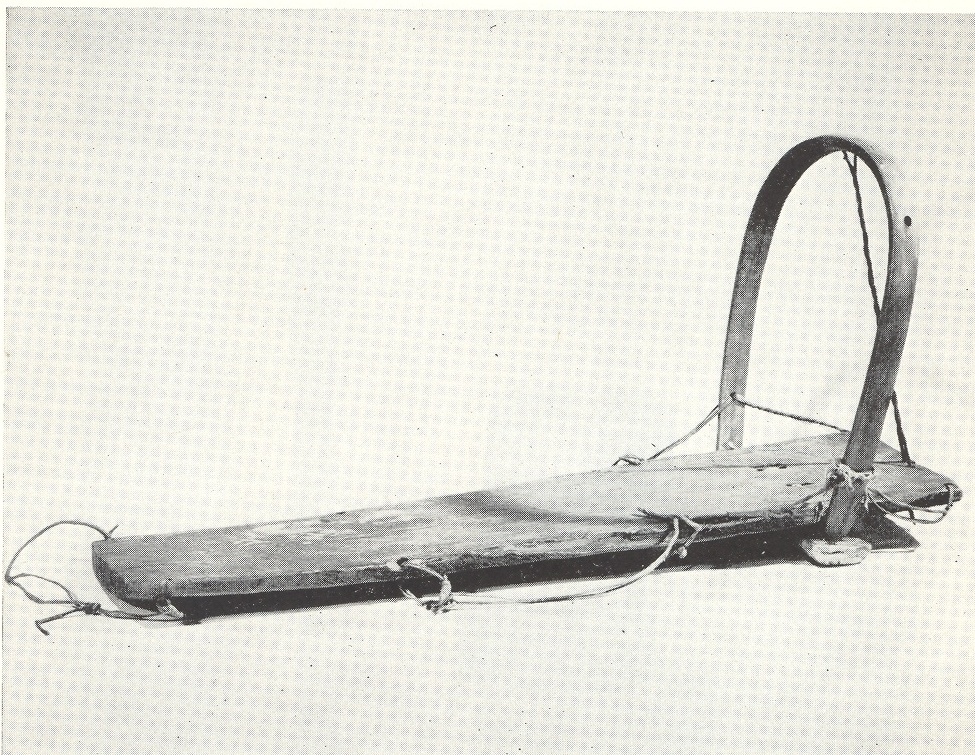

The cradleboard is still in use in the Mexican Kickapoo village. It is believed that children who spend many hours in a cradleboard will have a straight back, sturdy legs, and a well-shaped head. In the hot dry months of summer, many mothers will place their children in hammocks as a cooler alternative to being bundled up in a cradleboard. The main frame of the cradleboard is constructed of a single piece of hardwood approximately 2 feet in length, 7-10 inches wide and less than an inch thick. Extending up and over the head portion of the board is a hickory hoop which provides shade and shelter. The hoop is decorated with items reflecting the sex of the child: young male Kickapoo infants would often receive a tiny bow and arrow while females’ hoops often had metal balls. Unlike other cradleboard styles, there are no foot rests on those of the Mexican Kickapoo, and leather thongs, rather than nails, are used in their construction. Mexican Kickapoo women do not carry cradleboards on their backs; they hold them in their arms or prop the cradleboard and child against a wall when completing daily tasks.

“Infant in Cradleboard”

Cradleboard (E55847)

(Ritzenthaler & Peterson 1956)

Miscellaneous

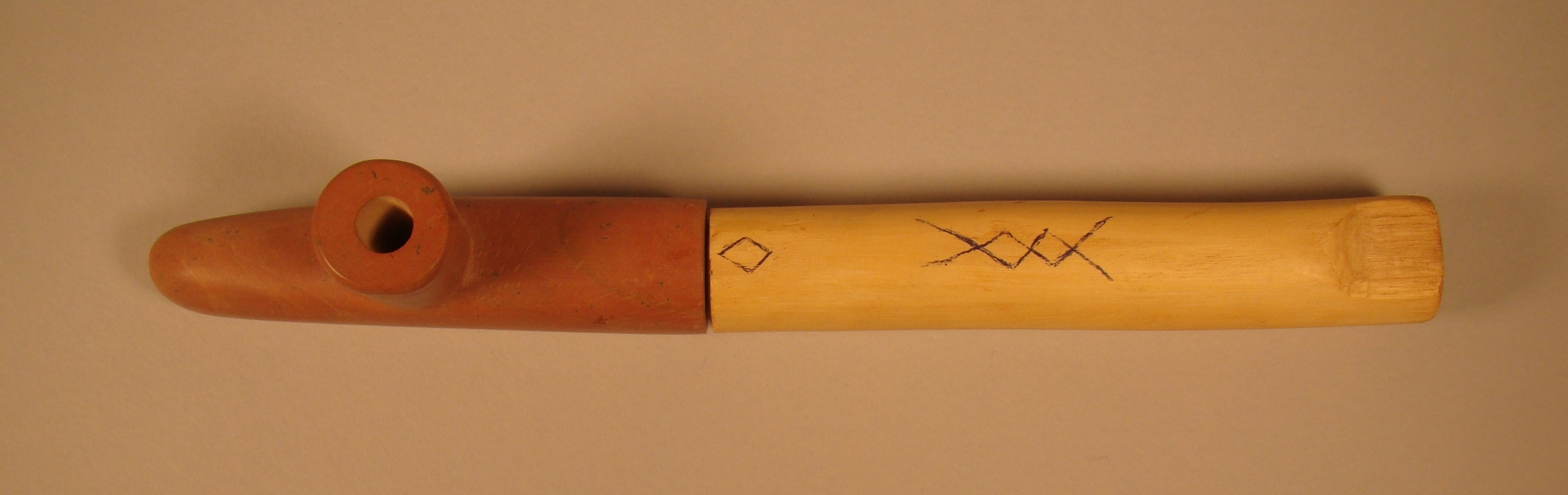

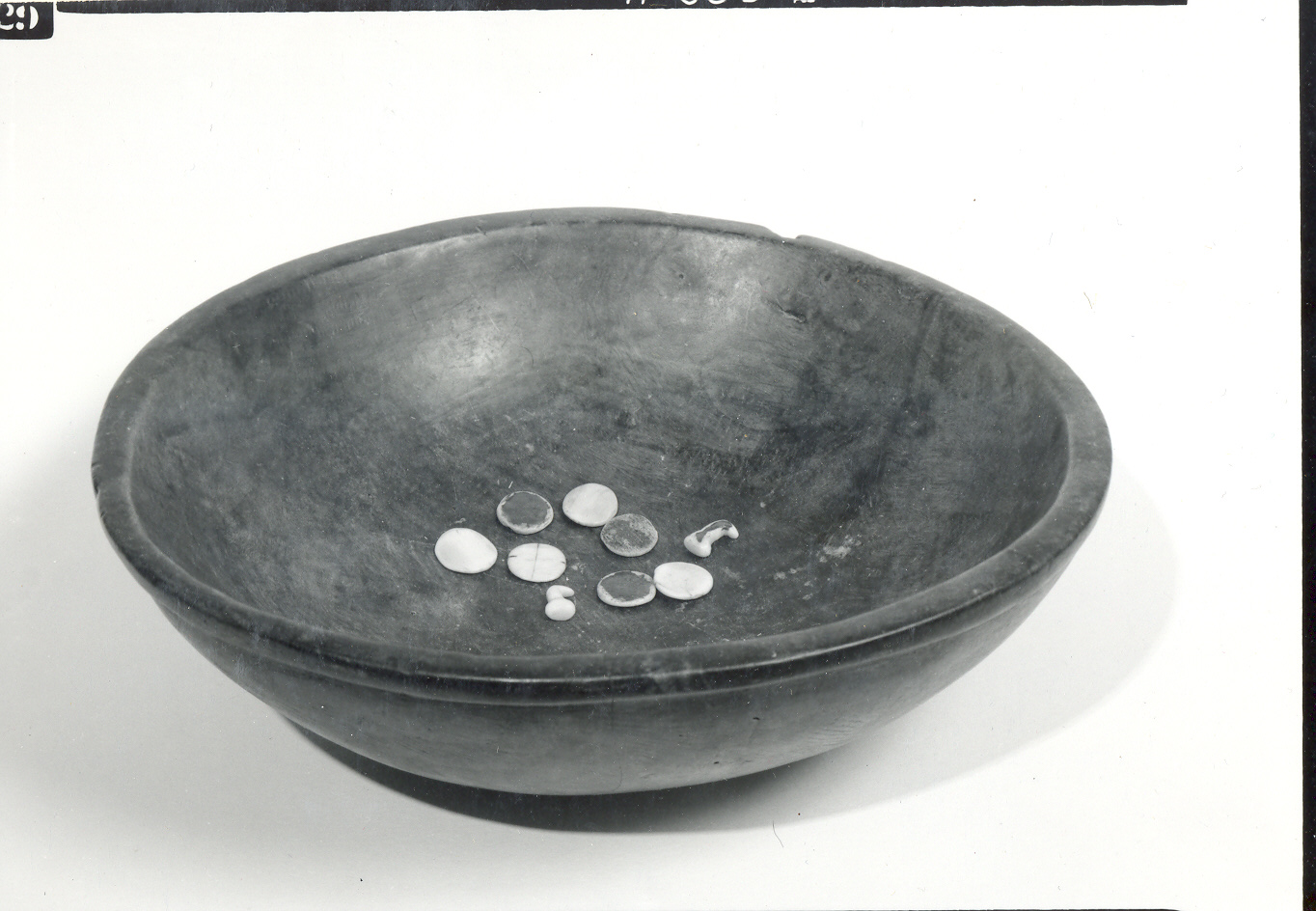

Other items included in the collection are a replica Jew’s harp, made by the silversmith specifically for the Latorres; a flute; a lacrosse stick; pipes; money bags; bowl and dice game; and a few dolls.

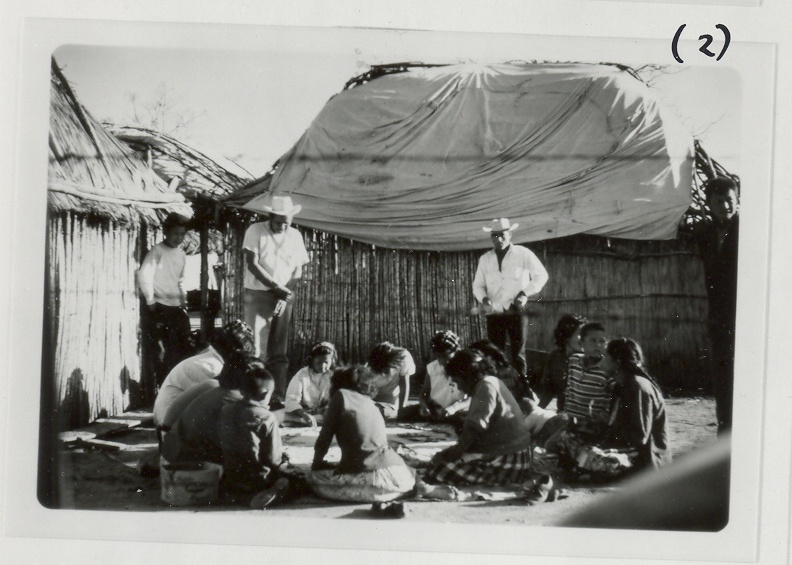

“Playing Bingo”

Pipe

Lacrosse Stick

Bowl and Dice Game

Jew’s Harp

Money Bag

Flute

From a young age, Mexican Kickapoo girls are encouraged to play with feminine toys such as dolls and to “play house” with each other. Dolls have also been used in witchcraft somewhat similar to how Haitian voodoo dolls are used. The doll is thought to represent the proposed victim, made more specific with personal items such as hair and nail clippings placed in the doll. The dolls pictured here were so well made that the women in the village feared they would be used for witchcraft. Fortunately the Latorres assured them that it was not their custom to perform such acts.

Male and Female Dolls

Collector Information

Robert Ritzenthaler (1911 – 1980)

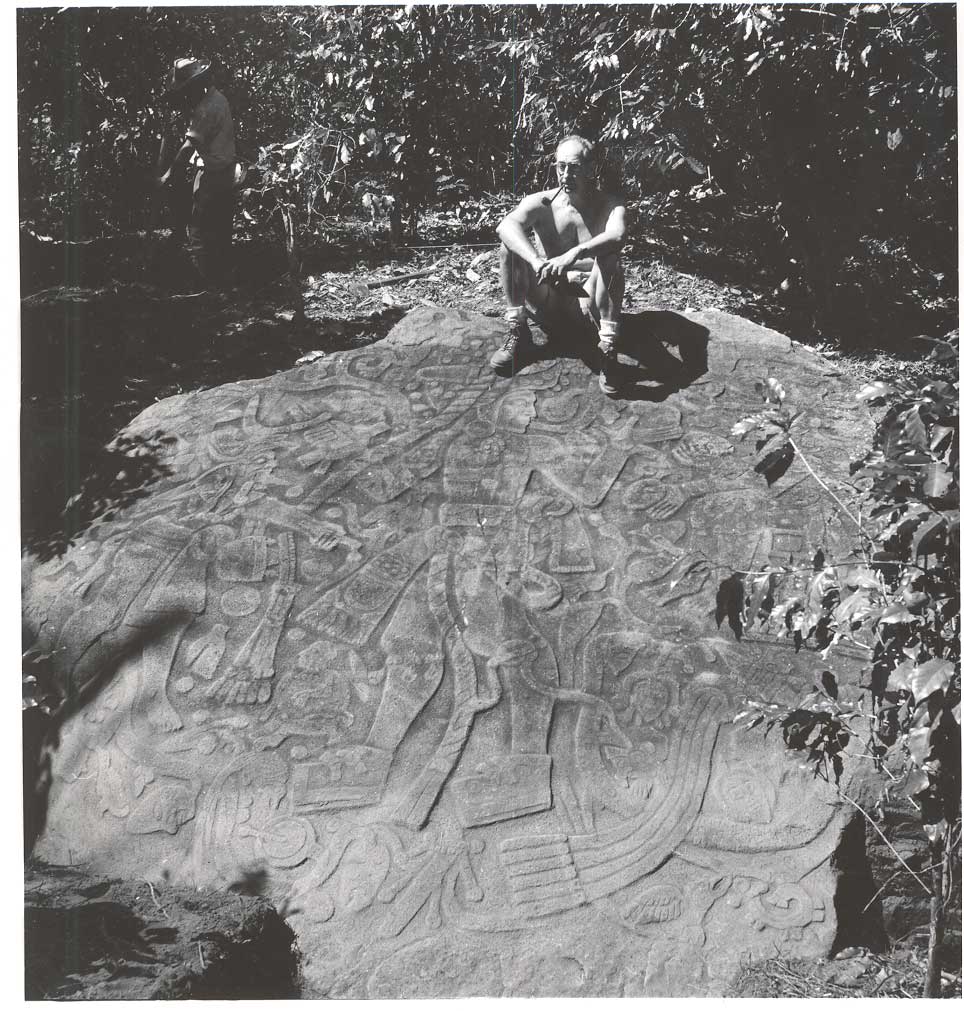

Robert Ritzenthaler’s career at the Milwaukee Public Museum began as a museum aide in the Anthropology Department in 1938. He had recently received a Bachelor’s degree in American History from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and had a teaching certificate from the Milwaukee Teacher’s College (now a part of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee). Late in his college career at Madison, Ritzenthaler took a class in anthropology and he was fascinated. He rounded out his college work with a Masters in Anthropology from UW-Madison and a Doctorate in Anthropology from Columbia University. Ritzenthaler succeeded W.C. McKern as MPM Anthropology department head in 1943 and he remained in this position until his retirement in 1972. Ethnographic fieldwork, Ritzenthaler’s preferred method of study, was conducted on several continents and with many different culture groups including the Oneida, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Mexican Kickapoo, native Palauans from the Caroline Islands, and the Bafut in Cameroon. He also took part in several archaeological digs at the Kincaid site in Illinois and the Wisconsin sites of Aztalan, Osceola, and Oconto as well as the southern coast of Guatemala. Along with his busy schedule at the museum, Ritzenthaler found time to teach anthropology and museum studies courses, at both UW-Madison and UW-Milwaukee. Though Ritzenthaler and his colleague Frederick Peterson spent only a few weeks with the Kickapoo, they managed to take film footage and collect photographic documentation of the tribe, as well as acquire items for the museum collections.

“Ritzenthaler Seated on Bas Relief - Guatemala Expedition”

Dolores and Felipe Latorre (1903 – 1999) & (1907 – 1997)

The Latorres, a husband-wife ethnography team, published the most comprehensive cultural account of the Mexican Kickapoo yet written. Both studied anthropology at the University of Texas and at the National University of Mexico. Dolores, a native of Spain, and Felipe, born in Chile and a retired Chilean air force general, spent 12 years studying the tribe in Coahuila. Taking Ritzenthaler and Peterson’s fieldwork as a cautionary tale, the Latorres spent more than 6 months residing in Muzquiz to gain the confidence of the Mexican Kickapoo. Their patience paid off and their fieldwork resulted in the publication of their book The Mexican Kickapoo. In 1975, the Latorres sold their collection of Mexican Kickapoo material – approximately 200 pieces – to the Milwaukee Public Museum. They were in the process of moving to a smaller space and they simply did not have enough room (Lurie 1976). The Latorre’s ethnographic documentation of the Kickapoo, as well as manuscript notes and other archival information, can be found at the University of Texas.