Cosmic Curiosities

"The search for truth and knowledge is one of the finest attributes of man,

though often it is most loudly voiced by those who strive for it the least.”

- Albert Einstein

Cosmic Fireworks

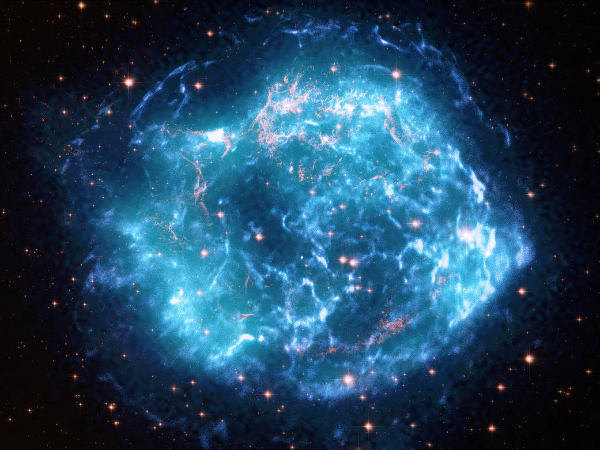

Exploding fireworks on July 4 are nothing like the cosmic “fireworks” in space. (There are no actual fires; space is a vacuum.) However, distant supernovae are often called cosmic fireworks. They resemble a big blast from one of our pyrotechnic displays.

Fires on Earth need oxygen; it’s a chemical process. A candle flame’s heat vaporizes the liquid wax, or turns wax to gas. The hydrogen and carbon gases are drawn up into the flame. They then react with oxygen in the air to create fire light. In addition, this process creates heat, water vapor, and carbon dioxide.

The explosion of fireworks is also an exothermic reaction, like a candle. “Exothermic” simply means a reaction where energy is released in the form of light or heat. For fireworks, the fuel (various chemicals) oxidizes, or burns, quickly, causing a great buildup in pressure that eventually leads to solids and gases bursting across the sky in colorful patterns.

Shakespeare once wrote, “Doubt the stars are fire.” Back 400 years ago, no one knew what process made the stars shine at night. It would be logical to think that perhaps stars were distant fires in the sky. Today, we know stellar light comes from nuclear fusion—which is very different from a chemical reaction. Chemical reactions are about making, breaking, and rearranging bonds between atoms in molecules. Nuclear reactions transform the inner workings of the atom itself. We live every day mainly by chemical reactions and not nuclear reactions.

Stellar workings: nuclear fusion vs. gravity

Every shining star is a tug of war between nuclear fusion and gravity. The inward pull of gravity crushes the star, making it smaller and smaller. The outward push of fusion fights back. This delicate balance in our sun will last another five billion years.

Who discovered a star’s inner workings of fusion? Well, most major discoveries are rarely the work of one person. In 1920, British astronomer Arthur Eddington was the first to suggest a star’s energy comes from the fusion of hydrogen into helium. In 1925, Ceclia Payne-Gaposchkin discovered stars are comprised mostly of hydrogen. As nuclear physics grew, Hans Bethe precisely identified the "proton-proton chain" that powers a star in 1939. And their work was based on Ernest Rutherford, who unlocked many secrets of the atom and the astonishing forces that could be unleashed from the atomic nucleus.

To make nuclear fusion, you just need enough pressure or heat to squeeze the nuclei of the atoms close enough that they overcome their electromagnetic repulsion and bond into a single nucleus. A star’s pressure comes from its size—and thus, gravity. Its immense mass crushes everything inward to give birth to a star.

We experience this amazing nuclear process every day as sunlight.

Astronomical photographs of faraway supernovae may look like our July fireworks, but this cosmic explosion is the result of the nuclear fusion stopping within a massive star.

As we saw, stars balance gravity and nuclear fusion—but stars can run out of fuel. The massive stars live quickly—just millions instead of billions of years. When they have exhausted their light and are left with a dense iron core, the star stops; there is no more fuel to push the star outward. Gravity takes over. In a split second, the enormous star collapses upon itself. The speeding, falling gas then rebounds off the heavy, jam-packed iron core. This creates the explosion we call a supernova.

Writing about cosmic fireworks has given me one final thought: Could there be chemical fires out there in space? Maybe there is an alien planet with an oxygen atmosphere like Earth that has natural fires, and an intelligent life form has learned to make fire on this planet—maybe even create fireworks? Just a thought…

Constellation Creation

How many constellations have been imagined from the stars above? Who knows! There are probably thousands upon thousands if you count every stargazer who ever looked up at the sky and said, “I see a _______ !”

In 1922, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) established a modern list of 88 constellations to fill up our night sky. In 1928, they added exact borders. Most constellation names are in Latin, but most have a common English name like Draco the Dragon.

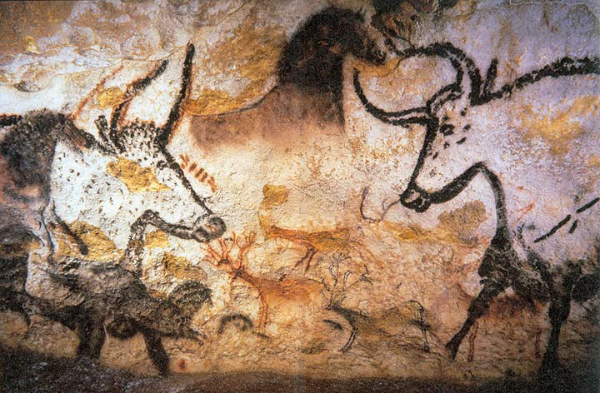

Depiction of aurochs, horses, and deer; Montignac, France

One of the earliest pieces of evidence of constellations in human history occurred 17,000 years ago, in the Lascaux caves in present-day France. Some of these paintings could also be the representations of star patterns they saw in the sky. Additional rock art found in Paleolithic caves could be ancient constellations. But how did we come to the list we have today?

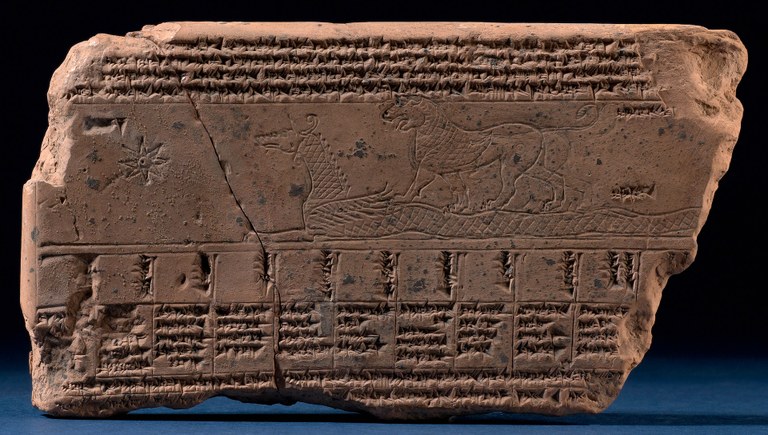

Many of our current constellations started around 3000 BCE in ancient Babylon. They were first inscribed stones and clay tablets. Additionally, these stargazers also tracked the five visible planets as well as the sun and moon, which were seen as gods. These solar system objects all follow a fairly narrow circle through the starry sky called ecliptic. This is because our solar system is generally flat—like a pancake. The background stars of the ecliptic are called the zodiac.

The 12 zodiac constellations were special. The movement of the sun, moon, and planets through the zodiac constellations were seen as signs from the gods above.

Late Babylonian astrological tablet with drawings of constellations and planets, 2nd century BCE

The close tracking of the sun and moon through the zodiac constellations allowed the Babylonians to track upcoming lunar and solar eclipses. Their predictions were fairly accurate for the time of an eclipse, but not as good for location. Accurate eclipse prediction would not come until Edmund Halley’s prediction of a solar eclipse that crossed over England in 1715.

In 150 CE, a Roman-Egyptian astronomer named Ptolemy took the existing constellations from Babylonia and Greece and formed a sky chart of 48 constellations that exist in our night sky today.

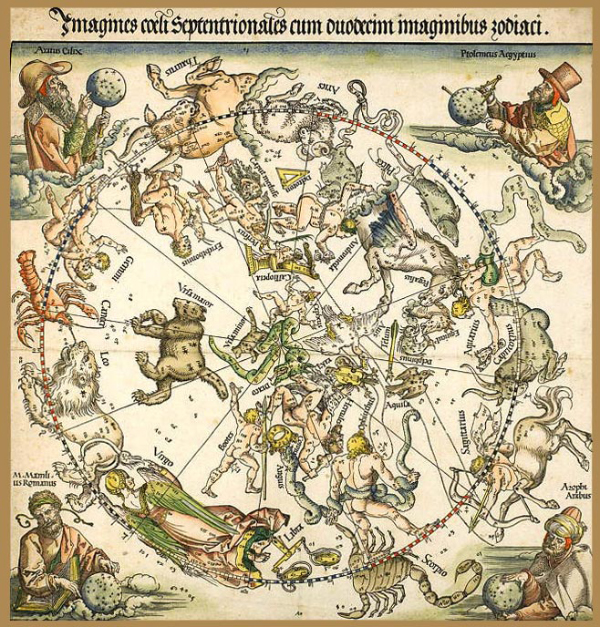

Star map by German Albrecht Dürer, 1915

One of the first celestial sky maps was drawn in 1515 by Albrecht Dürer. They were first based on Ptolemy’s 48 constellations.

When European explorers mapped the stars of the southern skies, they created new constellations. They also filled gaps between the traditional constellations. After this, Eugène Joseph Delporte drew up boundaries of the now 88 constellations so that every point in the sky belonged to one constellation.

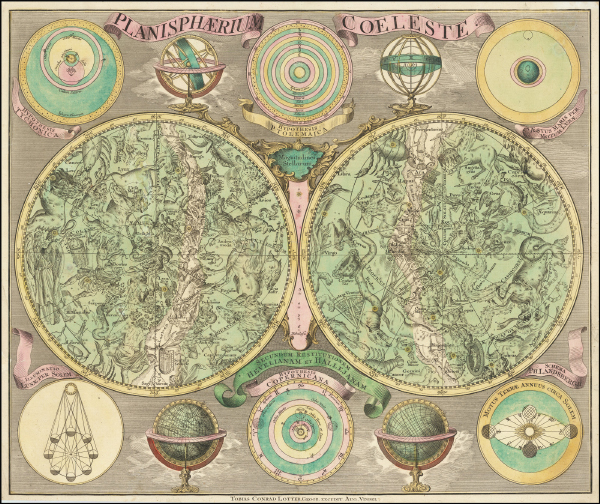

Tobias Lotter, a German publisher and cartographer drew many new maps of Earth as explorations across the globe became commonplace. With many of the new constellations that were being identified, Lotter included these in a “new” celestial map of both the north and south hemispheres in 1772.

Star map by Tobias Lotter, 1772

Lotter’s sky map was not the final drawing of the 88 constellations we have today, but it was very close. One big change was the break-up of the huge constellation Argo Navis. This mighty ship comes from an ancient Greek myth where Jason and the Argonauts search for the Golden Fleece. The constellation was split into three constellations: Puppis, the poop deck; Vela, the sail; and Carina, the keel.

It’s been 101 years since the constellations were finalized. One wonders if we will ever change these official sky designations. Remember, on your own, or with family or friends, you can always make up your own constellations!

Where to Stargaze in Wisconsin

In the Planetarium, it is always a clear night! During the Wisconsin Stargazing program, we leave the Milwaukee lights and go to the country where the change in the sky is drastic. Where exactly should you go to see the real sky like that? Where can you see the Milky Way and the constellations in all their glory?

While there are many places to stargaze, these five stand out because of their magnificent views:

- Newport State Park – Newport State Park is the ultimate stargazing destination in Wisconsin. It is designated as a Dark Sky Park by the International Dark Sky Association and is one of only two parks with the status in the Midwest. It is at the end of the Door County Peninsula, far from any light pollution. If you want to see what the night sky looks like, a trip here is a must!

- Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest – The Chequamegon-Nicolet is also very dark. It has the same level of darkness as Newport State Park. Away from all towns and cities, the sky can light your way at night. It is a large forest measuring more than 1.5 million acres. With that size, there are plenty of places within the Chequamegon to enjoy the night sky. Plus, there is something magical about watching the stars glitter through the trees!

- Apostle Islands National Lakeshore – The Apostle Islands are on Lake Superior in Northwestern Wisconsin. As a remote location, light pollution is minimal. The lake provides a perfect foreground for your next stargazing adventure because nothing blocks your view of the night sky. Make it to one of the islands on a clear night, and you will not be disappointed.

- Devils Lake State Park – If you hope to stargaze from your campground, go to Devils Lake State Park. The lakefront offers an unobstructed view with stars reflected in the water. Light pollution from Madison is visible on the horizon, but it does not stop the Milky Way from coming out in full force. The park hosts occasional stargazing programs with telescopes, so watch for those for a guided experience.

- Lapham Peak State Park – For a place closer to Milwaukee, Lapham Peak is the place to go. It is part of the Kettle Moraine State Forest. Though close to the big city, the views here are magnificent. The tower lookout allows stargazers a better view by allowing them to go above the trees. Plus, the park is open to stargazers year-round. They also host a monthly program with a telescope for those wanting to dive deeper!

Before you go stargazing, check the weather and maybe even scout out a stargazing spot during the day to help your journey go smoothly. Having a stargazing app or two downloaded does not hurt either, so constellations and planets will be easy to find. May your skies be clear and your stars bright. Good luck on your stargazing adventures!

Space in Sixty Seconds

Explore fireworks in the sky near and far!

Sky Sights

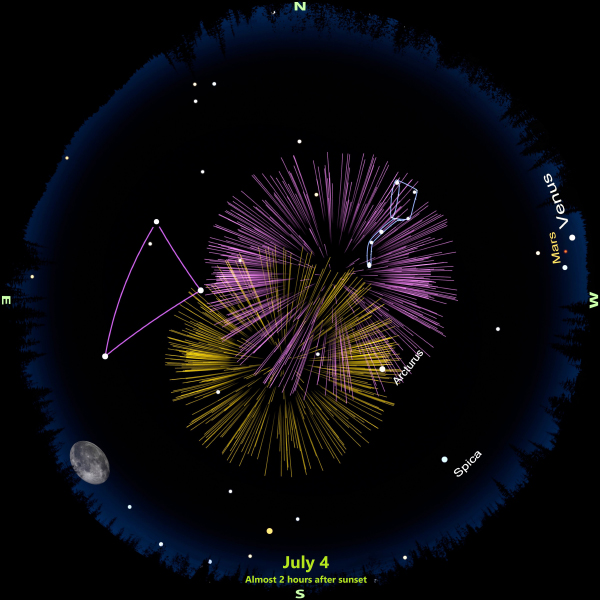

Catch the full Moon rising about one hour after sunset on July 3. On July 4, it rises about one hour, 45 minutes after sunset—when the fireworks are finishing.

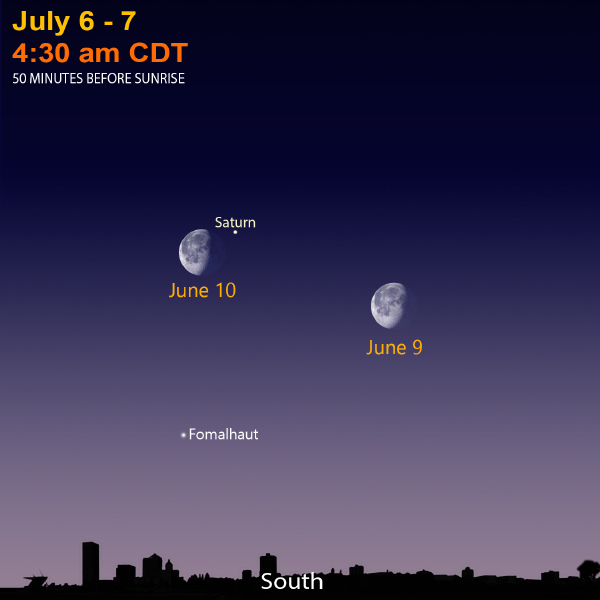

Saturn is still best seen in the morning sky. The Moon passes by on the mornings of July 6-7. For night owls, by the end of July, Saturn will be visible in the southeast about 10:30 p.m.

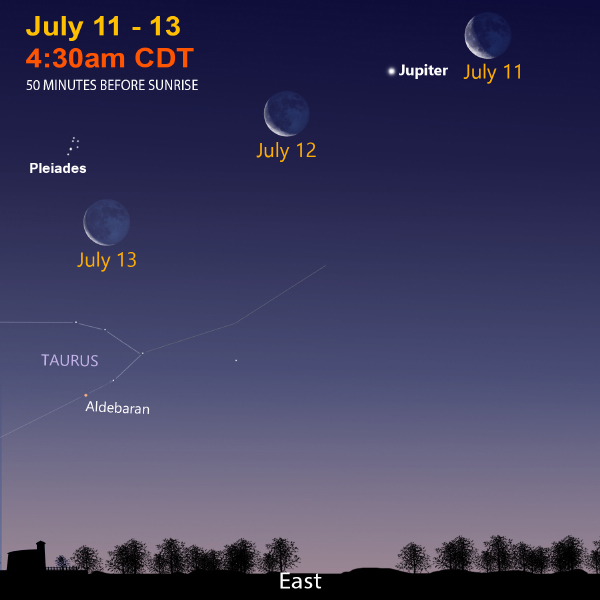

Jupiter is eye-catching in the eastern morning sky. Look for the Moon shining nearby July 11-13.

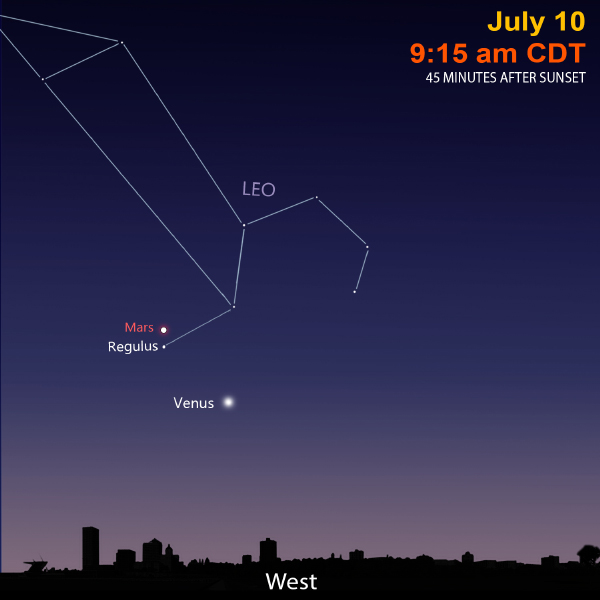

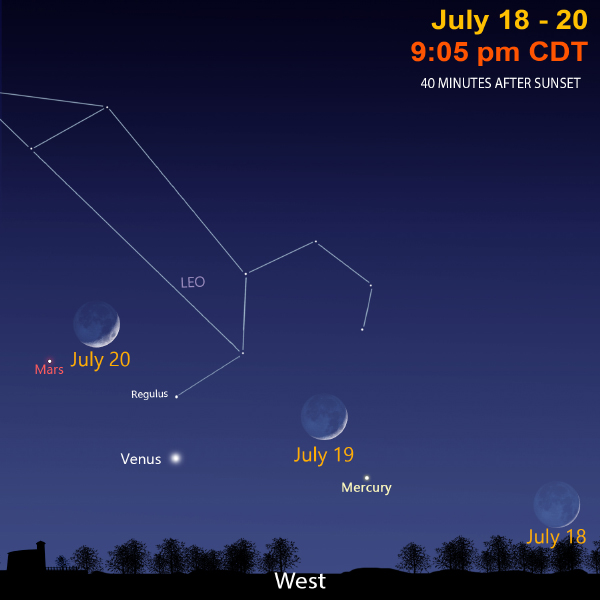

Venus and Mars set a little earlier after sunset. By July 31, Venus will be lost from view and then move into the morning sky by the end of August. Catch Venus and Mars near a crescent Moon from July 18-20. Notice the red planet pass the bright star Regulus in Leo.

Mercury will be visible but hard to see in the evening sky in late July.

July Star Map

Sign Up

Receive this newsletter via email!

Subscribe

See the Universe through a telescope

Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Follow Bob on social media

Twitter: @MPMPlanetarium

Facebook: Daniel M. Soref Planetarium