Cosmic Curiosities

“Snow was falling, so much like stars

filling the dark trees that one could easily imagine

its reason for being was nothing more than prettiness.”

- Mary Oliver, American Poet

Cosmic Fireworks

Image Credit: NASA

Meteor showers are breathtaking to watch, especially the Geminids peaking on the night of December 13 and 14.

It’s always best to escape city lights to really enjoy these “cosmic fireworks.” Lie back on a blanket or lawn chair and simply scan the skies above! Stay up late, or get up early if you can. The stars of Gemini—where the meteors radiate from—will start low in the east about 8 p.m. By midnight, this winter constellation will near the zenith. Before dawn, Gemini will shine high in the west.

We see more meteors between midnight and dawn because the Earth's surface is pointed in the same direction as its orbit. This means you are moving head-on through the dusty debris that creates the meteors. And this year, there will be no moon—meaning skies will be darker to see more meteors.

Watching a meteor shower can be both glorious and frustrating. After a minute or two, you spot one or two streaks of light. Then, a few more are seen; you want more fireworks! Impatience builds, hope escalates. Finally, another heavenly flash falls from the sky!

Image Credit: Town of Hamilton NJ Police Department

Who knows? You may get lucky and see a dazzling, exploding meteor like the one above. These bright ones that last a few seconds or more are called bolides, or fireballs. Most shooting stars, though, are faint and fleeting, lasting a second or less. Any ol’ night, you can see about five per hour, or one every 12 minutes on average.

Every December, the Earth passes through a debris trail left by an asteroid called 3200 Phaethon. As our planet hurtles through this dusty trail, the particles collide with the Earth's atmosphere at breakneck speeds—20 miles per second—igniting in a brilliant burst of light.

Hope for clear skies and temperatures that aren’t too cold. Stargazers can expect to see maybe 50 or more meteors per hour. If you are with a group of people, count the meteors together! See how many you can spot. Human eyes can only see about 25 percent of the sky—so you need at least four people to catch all the fireworks above you.

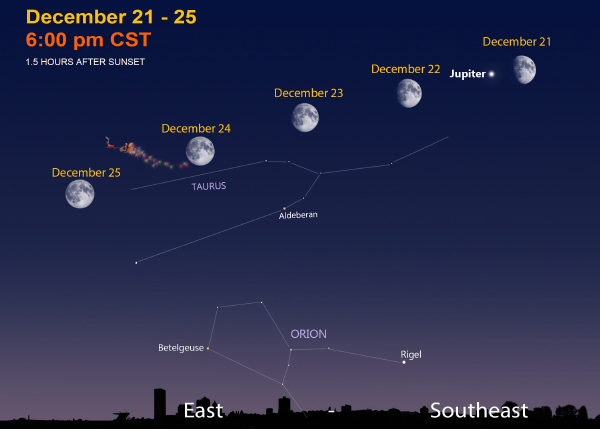

Orion Nebula

The Orion Nebula can be seen as a faint, fuzzy star. Look for the starlike object below Orion’s Belt to the right. It’s also known as the middle star of Orion’s Sword. With a pair of binoculars, or a small telescope, one can see more stars and gas in the nebula.

The constellation of Orion is a great winter friend. He is around most of the night. Look for his familiar belt and the two bright stars on each side—Rigel to the right and Betelgeuse to the left.

Orion Nebula Fly-Through, Credit: NASA, ESA, and F. Summers, G. Bacon, Z. Levay, J. DePasquale, L. Hustak, L. Frattare, M. Robberto, M. Gennaro (STScI), R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC), M. Kornmesser (ESA)

Astronomers and artists have turned all the amazing images of the Orion Nebula into a 3D journey. The Orion Nebula is a stellar nursery. It is the closest star-forming region to Earth. Hundreds of stars have been documented in the nebula at different points of a star lifecycle. It is a little more than 1,300 light years away from our eyes on planet Earth.

There are no exact boundaries to this nebula; it is what’s called a diffuse nebula. It does, however, have some structure: There is a region of ionized hydrogen centered around a bright star, Theta Orionis, within a young star cluster called the Trapezium.

The colors of the nebula are due to the abundance of the universe’s number one element: hydrogen. The temperature of the hydrogen determines whether it will be purple, pink, or red. The red color we see comes from ionized hydrogen that loses energy and releases photons. The more violet colors are the result of hydrogen radiation being reflected from massive stars in the core of the nebula.

Additionally, using a new James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have been able to get better imaging of the nebula. Recently, astronomers found planet-like objects floating without a star, changing our understanding of how planets might form. Head out on a clear winter’s night and watch stars being born!

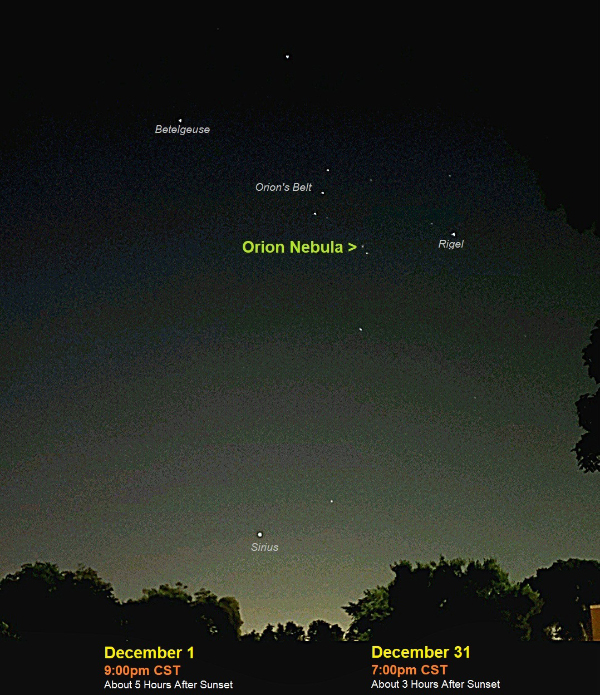

Calendar Check

Long ago, December was the tenth and last month of the year. In Latin, decem means “ten.” Think of the words “decade” (ten years) or “decimal” (a system of arithmetic based on the number ten, tenth parts, and powers of ten).

The roots of our modern calendar were born in ancient Rome. Their first calendar was established by king Romulus around 700 BCE. This system of tracking time consisted of ten months in a year of 304 days (obviously 61 days short of the modern 365 days in a year). The ten months were named Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December. The last six names were taken from the words for five, six, seven, eight, nine, and ten.

What’s up with the missing 61 days? Long ago, winter didn’t have any months. This colder dark time accounted for the missing days. Since winter is a non-growing season and not much happened, there was less need to track time. It was decided that this first Roman calendar would simply start anew on the first day of spring with the start of March, the first month. Today, we know December as the 12th month. Who added two more months? When? Why?

Soon after Romulus, another Roman king named Numa Pompilius is said to have added January and February to the calendar to start marking wintertime. However, January was not considered the start of the new year; that did not happen until around 150 BC. All these changes came about because of increased commerce and communication. This led to people needing to track time better.

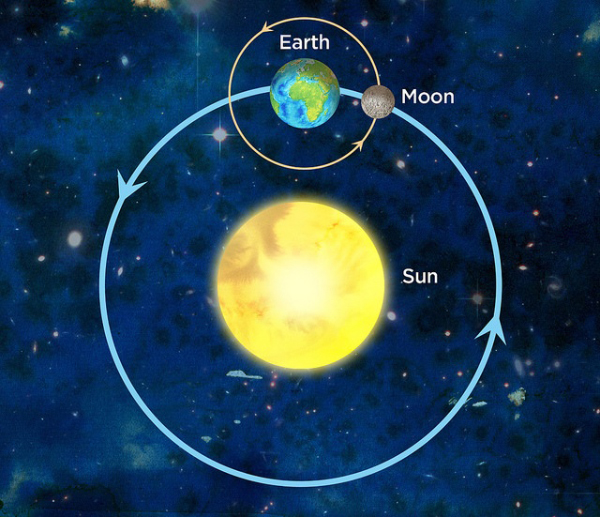

Tracking time and compiling calendars has never been easy. It all started with the beautiful and natural cycles of the sun, Earth, and moon. It quickly got complicated, and then we found out the sky cycles didn’t match up very well. For example, our moon’s monthly cycle of 29.5 days does not divide evenly into the Sun’s yearly cycle (Earth orbit) of 365.25 days. This led to many calendar problems—including the ancient Roman one with ten months. Today, we still have a tough time with time. Every year, we still switch our clocks back and forth, falling back to standard time and springing ahead to daylight savings time.

Space in Sixty Seconds

Spot a meteor shower, planets, and an old friend in the December sky.

Sky Sights

Venus can be easily seen in the southeast morning sky. A waning crescent Moon orbits by from December 8-10.

Saturn and the bright star Fomalhaut shine in the southwest after sunset. The Moon will help guide you from December 16-18.

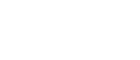

On the winter solstice through Christmas Day, December 21-25, check out our Moon shining near Jupiter and the bright stars of Taurus and Orion.

Mercury and Mars, once again, are too close to the sun to be seen this month.

December Star Map

Sign Up

Receive this newsletter via email!

Subscribe

See the Universe through a telescope

Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Follow Bob on social media

Twitter: @MPMPlanetarium

Facebook: Daniel M. Soref Planetarium