Cosmic Curiosities

“A single sunbeam is enough to drive away many shadows.”

-St. Francis of Assisi

June Solstice Nights

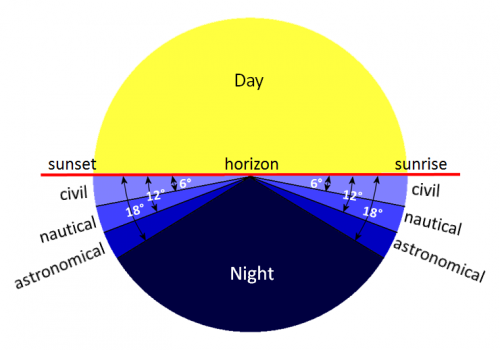

If you are an “early-to-bed/early-to-rise” type person—or even if you’re not—quality summer stargazing is difficult in Wisconsin. On the summer solstice, we have less than nine hours of nighttime. If you add the longer twilight hours, the starry night lasts less than seven hours. And if you define night as a pristine dark sky, it lasts only four hours!

If you are an “early-to-bed/early-to-rise” type person—or even if you’re not—quality summer stargazing is difficult in Wisconsin. On the summer solstice, we have less than nine hours of nighttime. If you add the longer twilight hours, the starry night lasts less than seven hours. And if you define night as a pristine dark sky, it lasts only four hours!

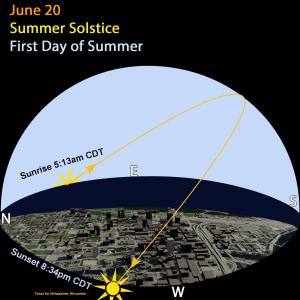

According to the diagram, a true dark night sky starts when astronomical twilight ends. On June 20, the summer solstice, that’s near 11:00 p.m. CDT in the Milwaukee area. This is when the sun is 18 degrees below the horizon and we are in Earth’s darker shadow.

At this point, human eyes can now spot the faintest stars possible. Of course, any two eyes need to be far from street lights and under a moonless sky. Astronomical twilight ends about 3:00 a.m. when the sky starts to brighten slightly. That leaves us with a dark night of only four hours. In winter, true dark-of-night lasts almost 13 hours.

At this point, human eyes can now spot the faintest stars possible. Of course, any two eyes need to be far from street lights and under a moonless sky. Astronomical twilight ends about 3:00 a.m. when the sky starts to brighten slightly. That leaves us with a dark night of only four hours. In winter, true dark-of-night lasts almost 13 hours.

Of course, there is much to see shortly after sunsets and before sunrises. Venus can be spotted with the sun in the sky, but it is not easy. Can you see it in the photograph? Bright planets and stars generally can be seen 40 minutes after sunset or before sunrise. This is when civil twilight ends and starts with the sun six degrees below the horizon.

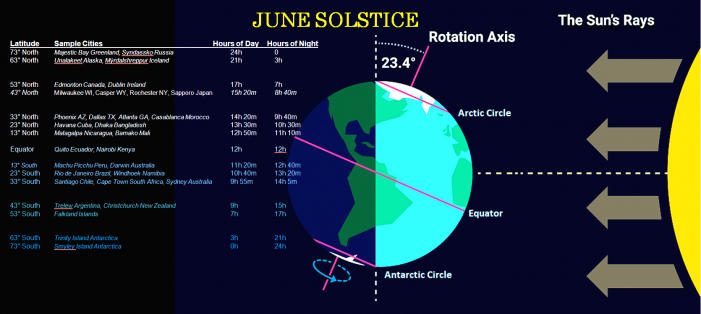

If you desire a longer summer night sky, you need to head south! Notice in the diagram how nighttime decreases if you head north and increases if you travel south.

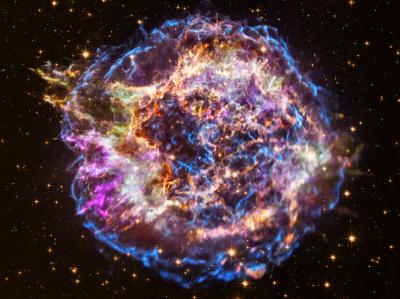

The Cass A Mystery

Last month, we toured the Veil Nebula—the ruins of a giant star that went supernova 7,000 years ago. This month, we travel back in time to explore Cassiopeia A, or Cass A, another star that furiously flared when it ran out of fuel about 330 to 350 years ago—making it one of the youngest supernovae in the Milky Way.

Last month, we toured the Veil Nebula—the ruins of a giant star that went supernova 7,000 years ago. This month, we travel back in time to explore Cassiopeia A, or Cass A, another star that furiously flared when it ran out of fuel about 330 to 350 years ago—making it one of the youngest supernovae in the Milky Way.

Cass A was a red supergiant with some 16 times the mass of the sun. But then it ran out of fuel. It exhausted its hydrogen supply and could not fuse iron in its dense core; no other star can. With no power to hold itself up, Cass A collapsed very quickly. It then rebounded off the compact core and sent a shockwave through its outer layers that resulted in a titanic stellar detonation.

At the core today is a neutron star. It’s so amazingly dense, one teaspoon would weigh over a billion tons, or the weight of Mount Everest.

No one witnessed this spectacular event—except maybe one person, but that recording may not be true. This lack of sightings is strange because:

No one witnessed this spectacular event—except maybe one person, but that recording may not be true. This lack of sightings is strange because:

- Cass A was close. Today’s astronomers have studied the debris field and pinpointed its distance at “only” 11,000 light years (LY) away. For comparison, in 1572, the Tycho supernova was as bright as Venus and that blast was just a little closer at 9,000 LY distant. In 1604, the Kepler supernova was almost twice as far as Cass A and as bright as Jupiter, the second-brightest planet.

- Cass A exploded between 1660 and 1680. This was a time of great astronomical discoveries. The telescope had just been invented and many were exploring the skies above. Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini discovered many of Saturn’s moons during that time. A bright supernova usually lasts for months before it fades from view—plenty of time to be spotted by Cassini, or someone.

- There was one observation—possibly. It was made by English astronomer John Flamsteed who recorded its position as a dimmer star in Cassiopeia. But his marked position does not match Cass A’s location to the degree it should. Since no one else observed Cass A, maybe the astronomer’s finding was a mistake?

So why did no one—or next to no one—see the Cass A supernova? Blame interstellar dust! That explains the mystery of Cass A. With no dust, the Cass A supernova would have a rich history of colorful observations from many different people. In today’s world with thousands and thousands of amateur astronomers and backyard stargazers, the “new” dead star would have been noticed right away!

Sky Sights

Click maps to enlarge.

Mars and Venus can be spotted low in the west after sunset. The red planet is higher in the sky but much dimmer. Our neighboring planets are aligning closer and closer each night. Next month on July 12, they will be the width of a full moon apart. The Moon orbits by from June 11-13.

Mars and Venus can be spotted low in the west after sunset. The red planet is higher in the sky but much dimmer. Our neighboring planets are aligning closer and closer each night. Next month on July 12, they will be the width of a full moon apart. The Moon orbits by from June 11-13.

The June solstice occurs at 10:31 p.m. CDT on June 20. This is when the sun is directly above the Tropic of Cancer, which is 23.5 degrees north of the Earth’s equator. Here in Milwaukee, we have 15 hours and 21 minutes with the sun above the horizon.

The June solstice occurs at 10:31 p.m. CDT on June 20. This is when the sun is directly above the Tropic of Cancer, which is 23.5 degrees north of the Earth’s equator. Here in Milwaukee, we have 15 hours and 21 minutes with the sun above the horizon.

It’s always strange to think that after June 20, the amount of daylight minutes starts to shorten. No worries; the sun-time shrinkage is very slow and gradual. We never seem to really notice the shorter days until August. So enjoy summer’s start!

A sign of summer in the night sky is the constellation of Scorpius. Look low in the southern sky after sunset. The tail of the scorpion is difficult to see if you have any trees or houses blocking in your view of the horizon. Remember the story about Orion and Scorpius: Orion lost their battle and fled to the winter sky. The scorpion was rewarded with its position in the summer sky. Watch our Moon match the scorpion’s shallow arc across the sky from June 22-24.

A sign of summer in the night sky is the constellation of Scorpius. Look low in the southern sky after sunset. The tail of the scorpion is difficult to see if you have any trees or houses blocking in your view of the horizon. Remember the story about Orion and Scorpius: Orion lost their battle and fled to the winter sky. The scorpion was rewarded with its position in the summer sky. Watch our Moon match the scorpion’s shallow arc across the sky from June 22-24.

Jupiter and Saturn rise after midnight on June 1. By June 30, Saturn rises around 10:30 a.m. and Jupiter by 11:15 p.m. Watch a waning gibbous Moon move by on June 27-28.

Jupiter and Saturn rise after midnight on June 1. By June 30, Saturn rises around 10:30 a.m. and Jupiter by 11:15 p.m. Watch a waning gibbous Moon move by on June 27-28.

June Star Map

Sign Up

Receive this newsletter via email!

Subscribe

See the Universe through a telescope

Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Follow Bob on social media

Twitter: @MPMPlanetarium

Facebook: Daniel M. Soref Planetarium