Cosmic Curiosities

“If people sat outside and looked at the stars each night, I’ll bet they’d live a lot differently."

~ Bill Watterson, Comics Writer -- Calvin and Hobbes

When Dead Stars Collide

Last year, for the first time ever, gravitational waves were discovered.

Last year, for the first time ever, gravitational waves were discovered.

Gravity waves are ripples in space-time. They act much like water ripples in a quiet lake after you toss in a rock. No one actually sees space rising and falling; the spacetime jostling is extremely slight. These tiny gravity fluctuations come from extremely energetic cosmic events. A new, very sensitive detector had to be invented. It’s called LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory). LIGO gives us a brand new way to “see” the universe.

Two weeks ago, two ultra-dense dead stars, called neutron stars, smashed together, creating gravity waves. LIGO detected them, and so did our “old-fashioned” telescopes -- the first was NASA’s Fermi telescope which detected a gamma ray burst. This detection allowed follow-up sightings by 70 ground-based telescopes around the world and in space. This marks the first time we have captured a cosmic event with both gravity and electromagnetic waves.

Neutron stars are a result of a massive stellar explosion called a supernova. This happens when a giant star builds up a compact iron core from millions of years of nuclear fusion. Fusing iron devours more energy than the star can generate. This means the outward energy push from the core stops! Gravity takes over and the star implodes, collapsing onto the dense core. The rebound effect is the stellar explosion—the supernova. However, the star’s dense core is still there. Its pressure is so enormous that atoms are crushed out of existence. Only a dense pile of neutrons remains.

How dense is a neutron star? Imagine an immense 747 airplane compacted into a grain of sand. That’s a neutron star.

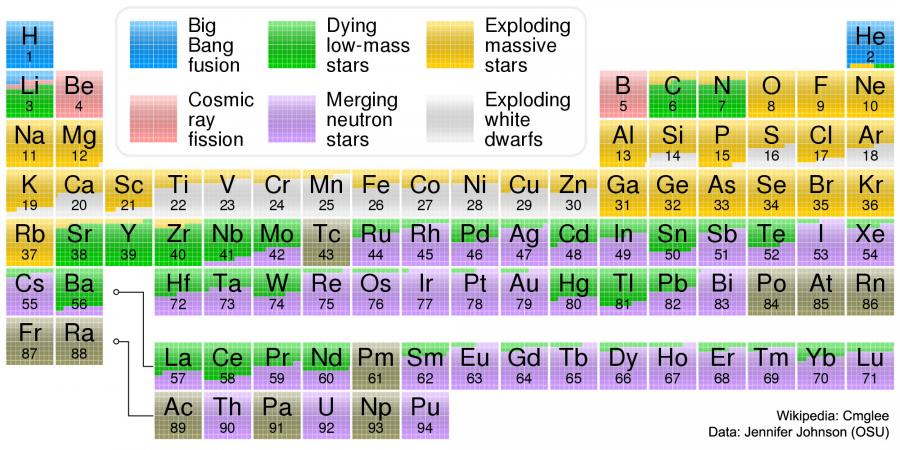

This recent neutron knockdown is known as a kilonova. Find the purple in the Periodic Table pictured above. Purple means these elements can be produced by the neutron stars smacking into each other. Most of the silver (47), iodine (53), and gold (79) on planet Earth came from one of these titanic collisions billions of years ago.

Amazing what can happen when dead stars collide!

Strange Moon Monikers

Moon names have grown in popularity lately.

About a year ago, I got a call from a news reporter about a “Black Moon” coming up. I confessed, I had never heard of it and quickly checked the internet. It turned out this mysterious moon was the second new moon in the same month. You can’t see a new moon because it’s between the Earth and Sun. No one seemed to know who exactly coined “Black Moon,” but it spread out across the internet and became a short media sensation.

Making a much bigger splash lately is the “Super Moon,” a slightly larger full moon due to its elliptical orbit, named by an astrologer in 1979. At first, no one paid much attention to it; then, somehow, somewhere, it gathered steam. For the last 10 years or so, Super Moon stories have made headlines across the globe. How did this mushroom? Was it the media? Was there a clever educator who promoted the Super Moon because he or she liked Superman? Who knows?

Making a much bigger splash lately is the “Super Moon,” a slightly larger full moon due to its elliptical orbit, named by an astrologer in 1979. At first, no one paid much attention to it; then, somehow, somewhere, it gathered steam. For the last 10 years or so, Super Moon stories have made headlines across the globe. How did this mushroom? Was it the media? Was there a clever educator who promoted the Super Moon because he or she liked Superman? Who knows?

Then there’s the more common, but still strange “Blue Moon.” It usually means the second full moon in the same month. The Moon does not turn blue! This Moon-moniker started in the 1940s and no one really knows why or how it got its colorful name. It’s very popular, though, as you will soon find out! In 2018, we will have two Blue Moons — one in January and one in March. On January 31, the Blue Moon will feature a total lunar eclipse, which leads us to our final moon story. . . .

Additional Moon names have also garnered headlines. Lately, I have heard historic Native American names for monthly moons spring back into the media: “Snow Moon” (February), “Strawberry Moon” (June), and “Beaver Moon” (November) are three that have made the news lately.

Moon names will probably continue to grow. Information spreads at the speed of light these days. Some terms may become trendy, some will be lost after one conversation. Be careful, though -- many of these monikers will not be rooted in science or astronomy. I will leave it up to you to see if there will be a “Green Moon” in April 2018!

What’s Up with Uranus?

Sorry, this article has no bad Uranus puns.

Sorry, this article has no bad Uranus puns.

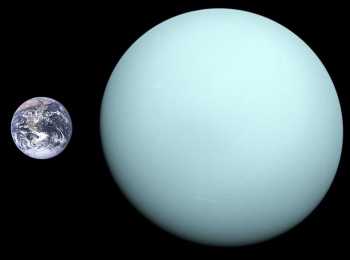

Recent internet reports suggest you could go outside and spot the planet Uranus in the sky. This made me scratch my head; I’ve never seen Uranus with just my eyes. It’s doable, I know, but pretty improbable. Uranus shines barely as bright as the faintest star -- this means you can only see it if you are exceedingly far from any streetlights. And the Moon can’t be around.

Uranus was discovered by William Herschel in 1781 using a telescope. I emphasize the word telescope because Uranus was seen by millions of people with their eyes, long before Herschel came along. No one knew this “faint star” was a planet. They never noticed it move slowly against the background of the more distant stars.

It is possible to precisely pick out Uranus with your eyes. However, you need a:

It is possible to precisely pick out Uranus with your eyes. However, you need a:

- clear dark sky;

- detailed and precise sky chart;

- red flashlight to read maps and maintain your night vision;

- boatload of patience.

Or, you can just get away from city lights and find the constellation Uranus is currently located (Pisces in 2017) and look up. One of those very faint stars is the planet Uranus. Congratulations!

Sky Sights

Saturn is still detectable low in the southwest after sunset. A sliver of a Moon orbits by from November 19-21. By early December, the ring jewel disappears from view. Saturn is in conjunction with the Sun on December 21.

Mercury joins the celestial show but will be closer to the horizon making the smallest planet difficult to locate.

_0.jpg)

Jupiter and Venus are very close on Monday morning, November 13, but very low in the eastern sky. Get up early and make sure you do not have any trees or houses blocking your view. Venus is descending and will be lost in the Sun’s glare by the end of 2017. Jupiter ascends and takes over dominating the morning sky.

Mars can also be viewed in the morning sky, but the red planet doesn’t come close to matching the brilliance of Venus and Jupiter. Look for the Moon to pass by from November 15-17.

Star Map

Download the November Star Map.

Download the November Star Map.

Sign Up

See the Universe through a telescope! Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Send an e-mail to Planetarium Director Bob Bonadurer at bonadurer@mpm.edu and place 'subscribe' in the subject line to receive the Starry Messenger and monthly star map.

![]() Follow Bob on Twitter @MPMPlanetarium.

Follow Bob on Twitter @MPMPlanetarium.

_0.jpg)