Northern vs. Southern Lacandon

Lacandon Indian, Chiapas, Mexico

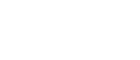

Mincho, Lacandon Indian, Chiapas, Mexico

There are two distinct groups of Lacandon, the Northern and Southern. The former live near the lakes of Najá and Mensäbäk; the latter live by Lacanhá Chan Sayab, near the ancient Maya ruins of Bonampak. The two groups differ slightly in customs and clothing and speak slightly different dialects. These cultural differences were most likely the result of different cultural influences over time, as well as isolation from each other (Boremanse 1998:7; McGee 1990:1; Palka 2005:52-54; McGee 2002:28-36, 40-43).

The most recognizable difference between the two groups is how they look and dress. The Northern Lacandon men have long hair with their bangs cut. They wear white tunics called xikul that extend to their knees. The women keep their hair long, generally braided with ribbons or bird feathers. The women wear colorful skirts underneath their tunics. The Southern Lacandon men and women dress in identical ankle length tunics and wear their hair long, parted in the middle. Today, many people of the younger generation now prefer to wear western clothes, and cut their hair short following western styles (Boremanse 1998:7; McGee 1990:1; Palka 2005:52-54; McGee 2002:28-36, 40-43).

The Northern and Southern groups speak two different dialects of the same Yucatec Maya language. Both groups use the same term, Hach Winik meaning "true people" to refer to themselves but they have different terms referring to each other. The Northerners call the Southerners "long tunics," or Chukuch Nok, while the Southerners refer to the Northerners as "far away people," or Naach-i Winik, and "other people," or Huntul Winik. Until the completion of roads in 1979, the Northern and Southern groups had minimal contact with each other and preferred to stress their differences rather than similarities. In the last 25 years, however, there has been more communication, trade, and intermarriage between the groups (Boremanse 1998:7-8; McGee 2002:28-36, 40-43; 71-124).

Settlement Patterns

Lacandon family in traditional house

Modern Lacandon house

Modern Lacandon house

Until the late 20th century, when housing patterns changed, Lacandon settlements were widely dispersed within the people's territory. Families lived singly or in small clusters in the jungle. Each household was made up of a husband, several wives, children, and extended family. Besides the house, there would be several other structures for storage, as well as animal pens and a god house. The houses consisted of wood posts supporting a thatched roof; there were no walls and floors were dirt. A clearing called the milpa was used for farming. Traveling between family clusters took about one day on foot. A cluster of households was not a permanent unit, but rather changed as young men and women got married and others split off to create new homes and clusters. (Boremanse 1998:50; McGee 2002:28-36, 40-43; 80-87).

Deforestation and missionary activities over the last century resulted in the Lacandon moving from small, well-dispersed houses to larger settlements with more families. By the mid-1970s, government policies were encouraging families who still lived by themselves to join one of the three major villages. Houses in these villages now have concrete floors and walls, and thatched or tin roofs. In addition, as many Lacandon converted to Christianity, they abandoned their polygamy for monogamous relationships, allowing additional wives to marry single men (Palka 2005:95-97, 238-240; Bormense 1998:26-27, 50, 101-124; McGee 2002:28-36, 40-43; 71-80, 87-104).

Political Organization

Lacandon Indian talking with representatives of coffee cooperative

The Lacandon live in a society without chiefs or priests. There is, however, an informal community leader. Respect and authority is based upon a man's ability to acquire wives, economic success, and knowledge of oral histories and religious rituals. The leader's word carries weight in social and religious matters; they act as advisors, mediate disputes and are in charge of initiating ritual ceremonies. The Northern Lacandon word for this individual is t'o'oh-il meaning "great" or "venerable" while the Southern Lacandon word for this is tah meaning "fierce" or "brave". The meaning of the word emphasizes the difference in the way this leader is perceived in each community. In the Northern community he exerts his authority through mediation and his ability to influence the gods while in the Southern community there is an emphasis on sorcery and intimidation. Today, in both communities, these leaders have become more like political representatives, responsible for negotiations with the Mexican government, private companies, farmers, and other outsiders (Palka 2005:244-246; Boremanse 1998:66-70; McGee 2002:28-36, 40-43,114-120; Thornquist 2006: pers. comm.).

Subsistence: Slash and burn agriculture/ hunting and gathering

Lacandon man in fields

Lacandon child doing household chores

Lacandon society today is characterized by a mix of traditional and modern technologies and subsistence practices. The Lacandon practice slash-and-burn agriculture and hunting and gathering. They earn money through trade and wage labor (Palka 2006:195-197; McGee 2002:47-51, 53-70, 72-80).

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a practice by which large trees are cut down and the underbrush is burned to create a farming plot. The Lacandon grow a variety of crops including corn, beans, squash, onions, lemon grass, tomatoes, chili, garlic, yams, avocado, and tobacco. A farm plot is used for about three to seven years before the soil is exhausted. It is then abandoned and a new farm plot is created. The Lacandon also harvest wild cacao, thatch for roofing, plant fibers for twine, clay for pottery, and wood for beams, dugout canoes and bows and arrows, and flint and chert for projectile points and hammer stones. All these items are traded for metal tools such as machetes, guns, iron axes and pots and pans, which are all used to a great extent. A variety of wild game including monkeys, rabbits, deer, and birds are hunted but as the forest becomes depleted, game has become scarce (McGee 1990:34-38; Boremanse 1998:8-9; Palka 2005:195-197; McGee 2002:47-51, 53-70, 72-86).

Modern Changes: Wage Labor

In the last century, some Lacandon have started working as paid laborers or as guides through the forest and sell handmade goods to tourists. In addition, they have sold some of their lands to the lumbering companies and used the money to buy vehicles and to construct houses, medical clinics, and stores. More recently, the Lacandon have been approached by fair trade coffee cooperatives interested in capitalizing on the booming worldwide coffee trade (McGee 1990:38-43; Palka 2005:197-199, 206-214; McGee 2002:47-51, 53-70, 72-80; Thornquist 2006: pers. comm.).

Indigenous Religion

Gods and God houses

Lacandon god house

The roots of the indigenous Lacandon religion can be traced back to the ancient Maya. The Lacandon worshipped a complex pantheon of deities relating to nature and the cosmos. Most religious ceremonies related to agriculture, fertility, pregnancy, childbirth, trade, and illness. During these ceremonies, the Lacandon prayed and offered food and copal incense to the gods. Every married man was expected to conduct these ceremonies for the benefit of his family. Women also had formal roles in religious ceremonies, most important of which was preparing ceremonial food and ritual offerings (McGee 1990:60; Boremanse 1998:xix; Palka 2005:247-8; McGee 2002: 28, 37-39, 125-129).

Every family or cluster of families would construct a god house next to their residence. The god house was constructed like the traditional Lacandon houses, with poles and a thatch roof and also a shelf for storing ritual items. God houses were also the place of community meetings, story telling, and the preparation of balché, an alcoholic ritual drink made from tree bark with sugar cane or honey added to it. (McGee 1990:44; Palka 2005:249-50, 260-263; McGee 2002: 28, 37-39, 136-138).

God pots and copal incense were two of the most important items in Lacandon religious ceremonies. A god pot was a clay bowl with an anthropoid head representing a particular god sculpted onto one side. It was through these pots that the Lacandon communicated with the gods; all offerings were transmitted to the gods through the god pots. The copal incense food and balché were all burned in the god pots as offerings. Balché is important because it was thought to be spiritually purifying, preventing and treating illness. Ritual flutes, drums, rattles, and conch shell trumpets were also important for calling people to the god house and for use in ritual dances (McGee 1990:44; Palka 2005:251-63; McGee 2002: 28, 37-39, 138-144).

Sacred Places

Maya Ruins at Yaxchilan, Chipas, Mexico

The Lacandon used to make pilgrimages to sacred places, such as caves and ancient Maya ruins. They would communicate with the deities and conduct rituals at these locations by burning incense in the god pots and leaving offerings. There are many caves along the shores of Lake Mensäbäk that contain shrines dedicated to specific gods. When new god pots were made, there was a renewal ceremony in which the old ones would be ritually disposed of in these caves (McGee 1990:55-59; Palka 2005:258-60, 263-268). The Maya ruins were believed to be the home of the gods, and when a new god pot was created, a stone from one of the ruins was placed in the center of the vessel to represent the body of the god (Boremanse 1998:xix; McGee 1990:57; Palka 2005:258-60, 263-268; McGee 2002: 28, 37-39, 129-136).

Loss of Indigenous Religion

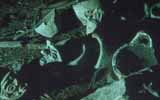

Deposits of gods pots in sacred cave, Lake Mensabäk

Abandoned god pots

Abandoned and collapsed god house

As a result of contact with missionaries the Lacandon became much more hidden and secretive with their religious practices. They often moved their god houses deeper into the forest and away from their homes to make it harder for others to find. Despite these attempts, many rituals and ceremonies were nevertheless abandoned. Many elders died of diseases before knowledge of rituals could be passed down and, in some instances, Protestant missionaries filled the gap left from the loss of elders. As a result of these cultural influences, many Lacandon converted to Christianity. In addition, the Lacandon ceased to use the ancient Maya ruins as places of pilgrimage and worship because of tourists and security guards (Palka 2005:272-75; McGee 2002:44-47, 150-152).

By 1960, there were no Southern Lacandon who practiced the indigenous religion; all had either converted to a form of Protestant Christianity or did not identify with any religious group. By the mid-20th century, very few god houses were left, and most of the god pots had been permanently deposited in the sacred caves. It was not until the late 1970s that the majority of those living in the northern villages began to convert to Christianity. As of this writing, there is only one individual who still practices the religion, making god pots and burning incense in prayer to the gods. Although the majority of the Lacandon do not practice their indigenous religion, they do still consider the caves, as well as the locations of several old god houses, to be sacred spaces ( Palka 2005:272-75; McGee 2002:44-47, 150-152; Thornquist 2006: pers. comm.).