The Village

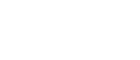

The Kickapoo village occupies an area of 22.4 hectares, or approximately one square mile. The structures are laid out in a systematic plan, with two roads running north to south crossed by two roads laid out east to west. Subsequent smaller roads branch off the main lanes. The homes in the village are fairly standardized; roughly the same size and shape. There are no large community center buildings or houses. In 1956 there were 56 occupied dwellings, all wigwams. The traditional Woodland wigwam is constructed with cattails and birch bark, but the move to Mexico and the lack of birch bark forced the Mexican Kickapoo to substitute additional cattail mats to cover the wigwam. In 1976, the Latorres counted 83 dwellings, 76 built traditionally and 7 built in the wattle-and-daub method common in Mexico.

“Securing Matted House Exterior”

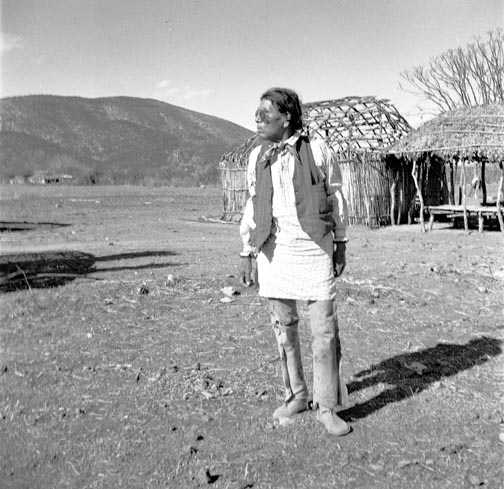

“Wigwam Frame”

There are two types of homes within a traditional Kickapoo village: a winter home and a summer home. The winter home is elliptical, 25 feet in length, 9 to10 feet high, and occupied from October to March. The summer home, by contrast, is 20 feet square with an 11 foot high domed top, attached to the exterior of the front facing wall is an overhang measuring the same width as the house and stretching out 8 feet from the wall face like an awning. This house is occupied from March until October. Openings on houses consist of a single doorway, always facing east, and a smoke-hole in the ceiling for the fire inside. The houses generally belong to the women, and with each new season they are in charge of rebuilding and recovering their homes. This is often done with the help of a few male family members who assist with the primary pole skeleton underneath the cattail mats. The mats that cover the house are made by women. Included with the upkeep of the house structure itself is the overall cleanliness of the household. Homes are free of litter and trash as well as clutter. As of 1976, concrete buildings, modeled after those seen amongst their Mexican neighbors, were becoming a more commonly observed occurrence in the Kickapoo village. Some additional buildings such as small stores called jacals were found in the village as well.

“Securing Matted House Exterior”

“Wigwam Frame”

People

Ritzenthaler and Peterson observed that the Mexican Kickapoo conduct themselves with considerable pride in “both action and poise” (1956:25). In addition to this proud exterior was an air of suspicion, also originally encountered by the Latorres upon their first months studying the tribe. Both groups of researchers attributed this to the history of Kickapoo contact with foreign influences. Ritzenthaler and Peterson also noted the frankness of the people as well as a good sense of humor.

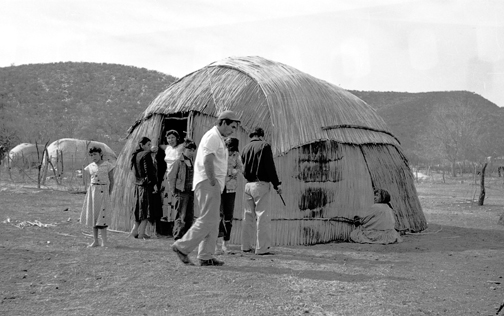

“Owner of Dance”

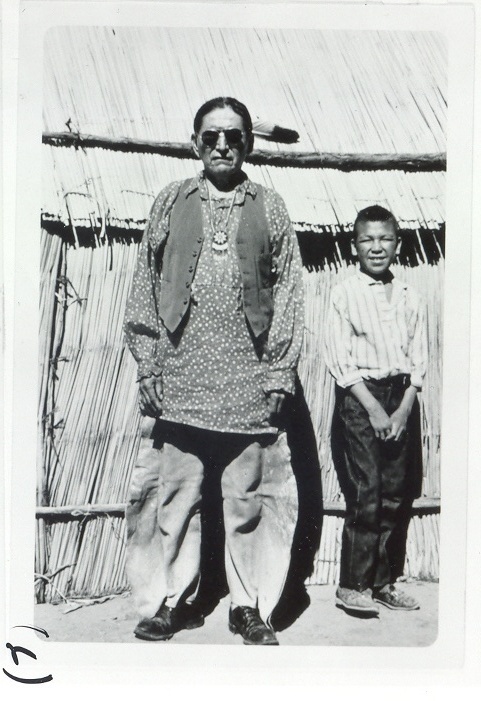

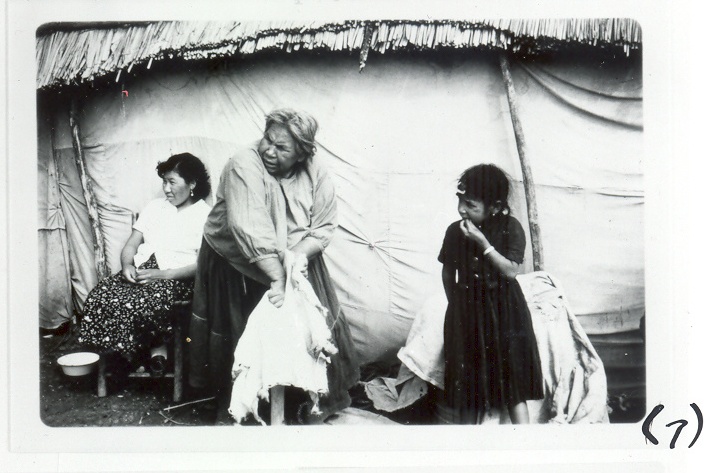

“Woman in Home”

“Contented Worker”

Dress did not appear to change much between the two studies. Men traditionally wore adorned calico print shirts with buckskin leggings, a breechcloth, a European style vest decorated with silver brooches, and moccasins (Latorre 1976). This style of dress was worn primarily by the chief, with a few exceptions made to accommodate the time of season and the weather. Other members of the tribe wore this style for various ceremonies and dances. The usual dress of the men is what both research parties referred to as “working clothes” consisting of blue jeans or khaki pants, cotton button-down shirts, and wool jackets for warmth. For many, the clothing was often acquired in surplus stores in the United States. The Latorres noted that the trend with some of the younger Kickapoo men was to dress like the Mexican Cowboys, complete with tighter, hip hugging Levis, wide-brimmed cowboy hats, and cowboy boots. It would stand to reason that t-shirts, sneakers, and ball caps would now be acceptable attire amongst male tribal members, evident from recent photos taken in Nacimiento (Rosales 2008).

“Man in Chief’s Outfit”

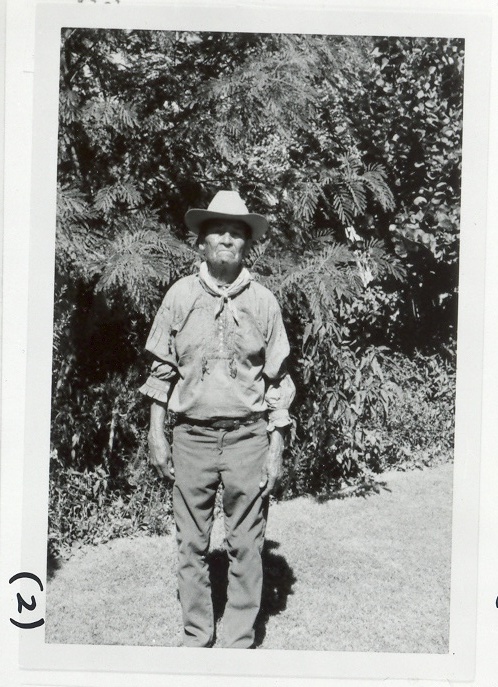

“Man in ‘Cowboy’ Attire”

“Man in ‘Working Clothes’”

Women’s clothing styles changed very little between studies and included skirts, blouses, and dresses of colorful cotton. It is possible that this style had been adapted from the pioneer women of the 19th century (Latorre 1976). Following similar trends as with men’s traditional dress, women’s outfits lack adornment such as beadwork and silver. Women did, however, wear jewelry: single-strand beaded chokers, silver bracelets, rings and earrings were popular. Variety in women’s dress was exhibited in the choice of footwear and outerwear. Many women chose to wear Western styles during their time spent in the States, but after returning to the village it was observed that they reverted back within a few days to the age-appropriate style of dress for a Mexican Kickapoo woman. Today, it appears that this standard may have changed quite a bit as it appears that jeans and t-shirts are also worn by female tribal members.

“Elder Woman’s Outfit”

“Women Outside”

“Young Girls”

Traditional male haircuts consisted of a long bob, parted down the center, and a long, thin queue in back. Similar to hairstyle trends in the States, this traditional style was just beginning to phase out in the mid-70s due to the appeal of longer hair.

“Young Man with Modern Haircut”

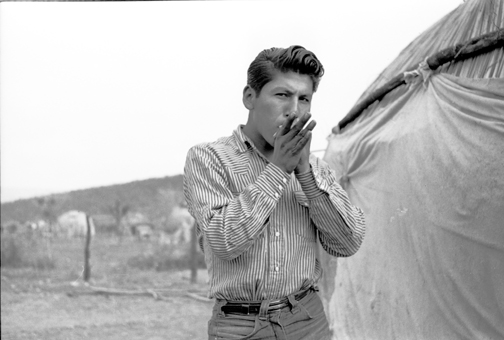

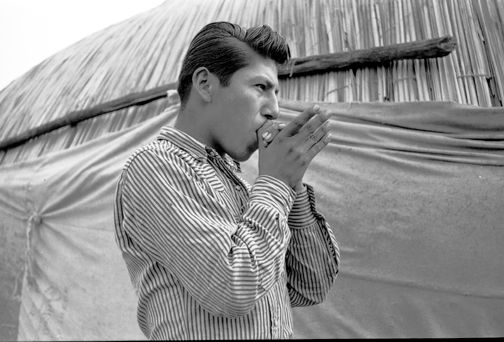

Shaving at this time was carried out with the spring from a .30-.30 Winchester rifle. The spring is rolled over the face, while the loops are continually opened and closed, pulling out hairs on the face of Kickapoo men. Most men are clean shaven, though the Latorres noted that some younger men wore moustaches, similar to those seen on Mexican men at the time.

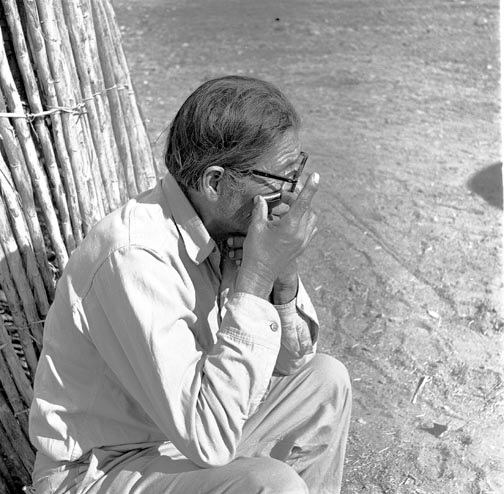

“Shaving”

The traditional hair style for adult women consists of a long braid, tied in the back by a ribbon. Ritzenthaler and Peterson also noted a top-knot design for younger girls, discarded only when they are of marrying age. The Latorres noted that this style was not a common sight. In the past, silver combs were worn in the hair but these too were observed less and less, particularly with the increase in travel to the United States. For women, long hair and plumpness are considered signs of beauty. Often after having children, women will strive to keep their weight up to maintain the ideal reached during pregnancy.

“Ladies and Children at Home”

The Mexican Kickapoo speak primarily traditional Kickapoo, with existing linguistic characteristics of the base Algonkian language, though more are speaking Spanish and even English. Many who speak either Spanish or English (sometimes both) act as contractors, interpreters and guides for the tribe. Those that speak English are often younger adults. Historically, the Kickapoo rarely attended school, but were often exposed to the language during their migration to the states. Foreign-influenced education and religion have been seen by the Mexican Kickapoo as corrupting influences on tradition, and have been met with extreme hostility in the past, such as the burning of several school buildings by the Kickapoo, as well as the near immediate expulsion of varying outside religious leaders from the village. This view is changing slowly since more Kickapoo are attending school.

Ritzenthaler and Peterson noted, and the Latorres concurred, that the young adults in town engage in what they called “courtship whistling.” Each young couple shares a distinct whistle known only between each other, as distinct as the individual tones someone uses to talk. The whistling is a form of communication between couples to verify when they will meet up in the evening. This was done formerly through the use of a flute, but since 1915 the courtship whistle has been used. The whistle is performed by pressing the lips up against the thumb knuckles of both hands cupped and blowing through the small hole created. The fingers and palms control the sound.

Subsistence

The Kickapoo were historically farmers and hunter-gatherers that supplemented their diet with buffalo hunted on the Illinois plains. Contact with Europeans began a whirlwind of changes in Kickapoo subsistence - from the introduction of the horse, to the migration of groups to new environments. During the 1940s, drought had devastated arable land available for farming and pasture, and fencing and hunting restrictions limited the supply of food and valuable animal skins. It was during this time that the Mexican Kickapoo turned to migrant labor. As previously noted, this was possible due to a safe-conduct paper issued to the tribe at Fort Dearborn, where tribal members, though recognized as citizens of Mexico, were allowed to venture into the United States with relative ease. In 1954, the primary sources of income were hunting and migratory labor. Other strategies such as trading and craft sales were supplemental economic providers. During the 1950s and into the 1960s the Mexican Kickapoo were sought by growers in different parts of the country when laws regarding Mexican laborers became more restrictive. By the time the Latorres arrive in the village, migrant labor was still the single greatest source of income.

Though it is not necessarily a primary source of income or subsistence for the Mexican Kickapoo anymore, deer hunting is regarded as a necessary, sacred act. As recently as the 1940s, the entire tribe would leave for months on long hunting trips. Primary catches sought included deer, bear, mountain lion, and peccary. Of lesser importance, though still hunted were muskrat, badger, rabbit, bobcat, fox, raccoon, wild turkey, pigeon and partridge. The numbers of these animals seen near the village have dwindled severely. The deer is considered the single most important animal in Kickapoo ceremonies. For an infant Kickapoo child to receive their tribal name, the father must bring four deer to the naming ceremony. This is now more difficult as the number of deer grows increasingly scarce in Mexico and is virtually non-existent in Texas.

“Drying Meat”

“Preparing Hide”

Though hunting is practiced primarily with modern firearms, the bow and arrow continue to be important symbols of Kickapoo culture. By the time a male child reaches the age of four in the Kickapoo community he receives his first bow and set of arrows, and practices many hours daily. Ritzenthaler and Peterson took note of the marksmanship of these young boys in their field notes, even managing to take film footage of the scene: “The storekeeper gave them two oranges which they shot at from about 5 paces. They almost always nicked it and several times hit it dead center. At 10 paces they were not so accurate but they came pretty close.”

“Boy with Bow and Arrows”

“Carving a Bow”

Adult Kickapoo bows are approximately fifty inches long, tapered at either end, and the arrows are about twenty inches long. Turkey feathers are attached with sinew and antler glue to one end of the arrow. The projectile heads are made from steel or brass placed in the opposite split end of the arrow.

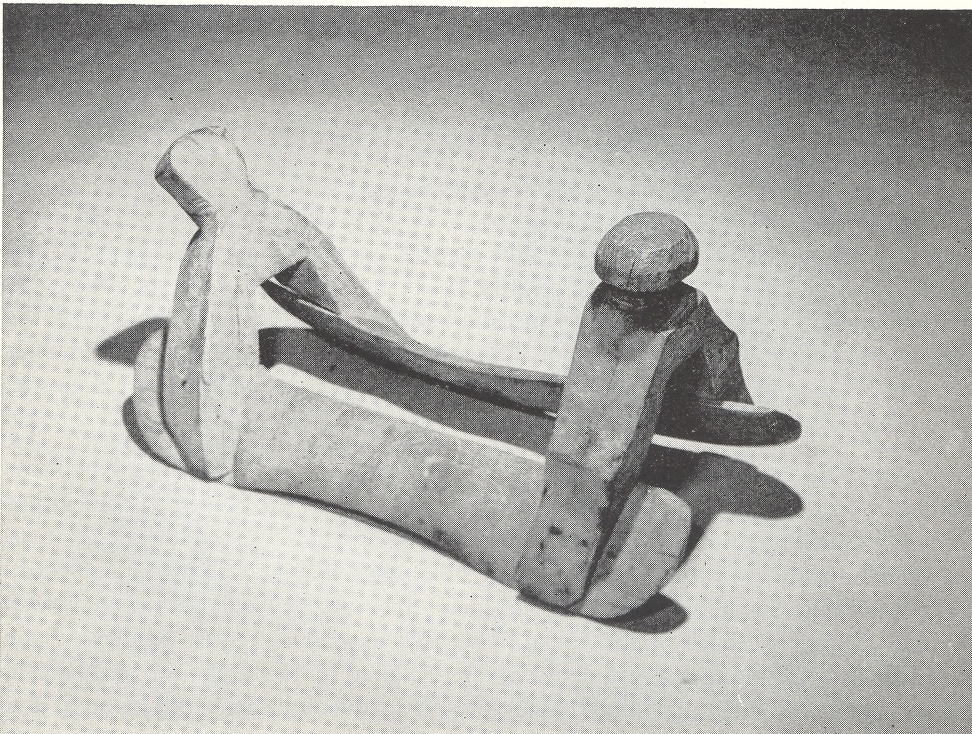

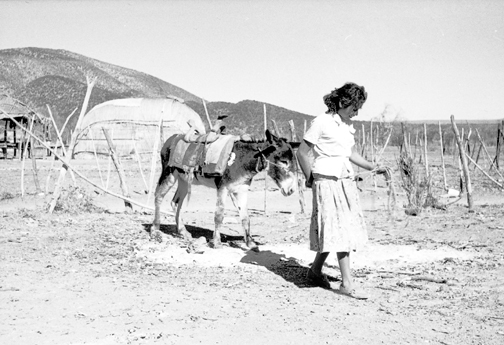

Saddle

“Girl with Burro”

(Ritzenthaler & Peterson 1956)

Other necessities for hunting include the deer call and the saddle. The deer call, made from wood, is worn around the neck by a leather strap and is about seven inches long. The owner blows into the tapered end and controls the sound made with the metal strips inside by opening and closing his hand over the hole. By fluctuating the sound that reverberates out of the piece, a good hunter can imitate the sound of a fawn in trouble. This succeeds in attracting not only deer but animals that prey on deer. The saddle of choice, used often times for hunting, is a wooden frame construction and similar to the design of the saddle tree used by Blackfoot Indians, called a “prairie chicken snare saddle.” Formerly, a hide of buffalo, deer, bear or peccary was placed over the saddletree, but today a blanket is used.

Social Structure and Ceremony

The Kickapoo family structure is matrilineal, or focused on the descent from female relatives. In terms of daily social structure this means that house compounds and living arrangements are often dictated by mothers and grandmothers. For example, a newly married couple will live with or within the compound of the husband’s mother. The Latorres observed that families, both nuclear and extended, are close and work together to provide for everyone. One informant stated that in terms of working and providing for his large family, “Among us, we share everything” (1976:142).

The tribe is also divided into fourteen separate clans, corresponding to aspects of the environment such as natural occurrences (Thunder), flora (Berry), and fauna (Black Bear). In 1970, the Latorres noted that there were formerly three additional clans, but the members had died by the time they surveyed the tribe. In the past, there was a rule that no Kickapoo could marry within their own clan, but this has since passed and younger tribe members marry whomever they choose. Children are named by clan leaders, which in turn dictate the ceremonial practices, rules, and activities that these youngsters will participate in as members of the community. Duties and privileges accompany clan membership. For example, chiefs were chosen from the Water clan at one point, while those of the Fire or Tree clans were responsible for food tasting during dances and ceremonies.

Along with clan designations are moiety assignments. The tribe is divided into two main moiety groups: Oskasa (“paints with charcoal”) or Kisko (“paints with clay”). The Latorres noted that the Kickapoo refer to these branches as partidos, or teams, because these designations are specifically used for dividing the tribe into teams for food competitions or ceremonial games (1976:156). Just as their names allude, one team is the black team and the other is the white team.

These clan and moiety designations are also important in religious ceremonies. Often only members of certain clans are allowed to prepare food, invite those of reciprocal clans to functions, or conduct the ceremonies themselves. The Latorres noted that Mexican Kickapoo ceremonies can be divided into four general categories: New Year clan festivals, the chief’s ceremonies, individual ceremonies, and adoption ceremonies. They noted that during the year there are thirty-three regularly scheduled ceremonies ranging from various naming ceremonies to the “Ceremony for the French Medal” and the winter feast for the dead. Also noted were eight ceremonies that were performed but did not fall on specific dates on the calendar.

“Buffaloes are Running Dance”

Music is essential to the ceremonies, and the drum is singularly important. Other instruments include the gourd rattle, sleigh bells, and the flute.

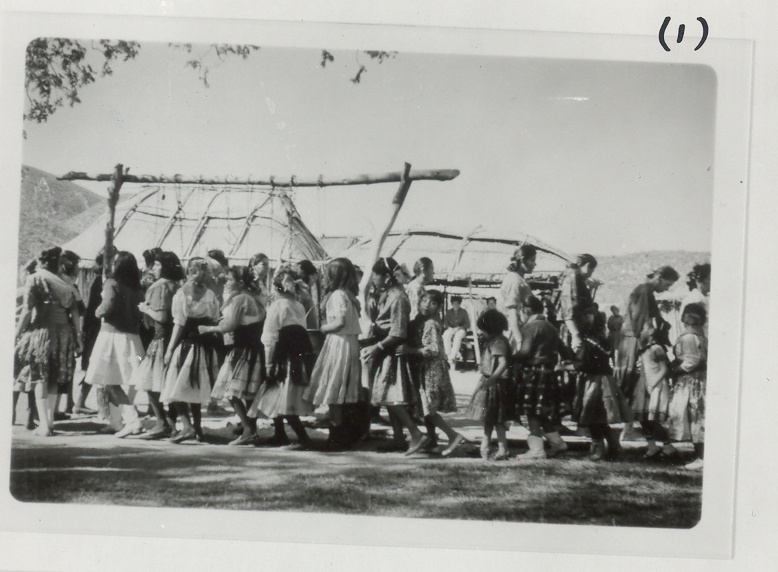

“Women’s Dance”

“Women’s Dance”