Cosmic Curiosities

"How can I hope to be friends

with the hard, white stars

whose flaring and hissing are not speech

but a pure radiance?”

- Mary Oliver, American Poet

Meteor Watching 101

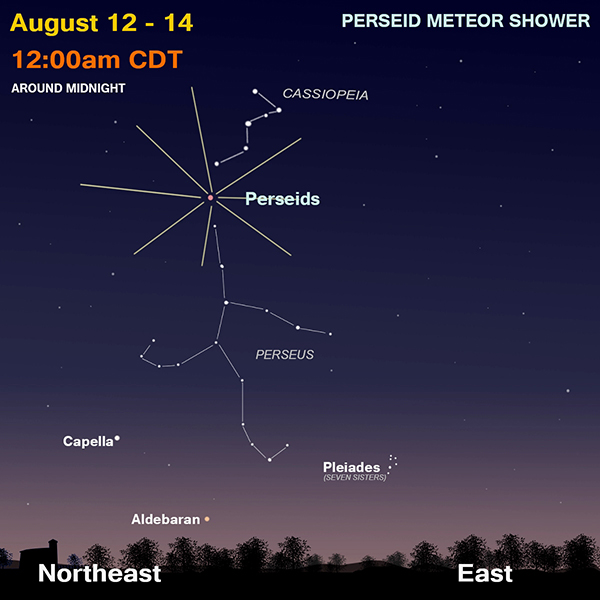

The annual Perseid Meteor Shower is just around the corner! It peaks the morning of Sunday, August 13, 2023. The night before and after should have more meteors than a typical night. This year, the moon is a waning crescent; its soft, serene light won’t interfere as much with the fainter meteors. Below are some tips and fun facts to enhance your night with the “shooting stars.”

METEOR SHOWER CHECKLIST

- Get up early! The best time to spot meteors is between midnight and one hour before sunrise. Sunrise for Milwaukee on August 13 is 5:55 a.m. CDT.

- Get away from city lights as much as possible.

- Count how many you or your group witness. Expect to see one “falling star” every two minutes on average.

- Bring bug spray! And a lawn chair or blanket.

- Lay down and look all across the sky. You do not need binoculars or a telescope.

- When you see a meteor, trace it back to where it came from. Most will radiate from the constellation Perseus, which is low in the northeast at midnight and high overhead one hour before sunrise.

METEOR MARVELS

- Most meteors are no bigger than a grain of sand.

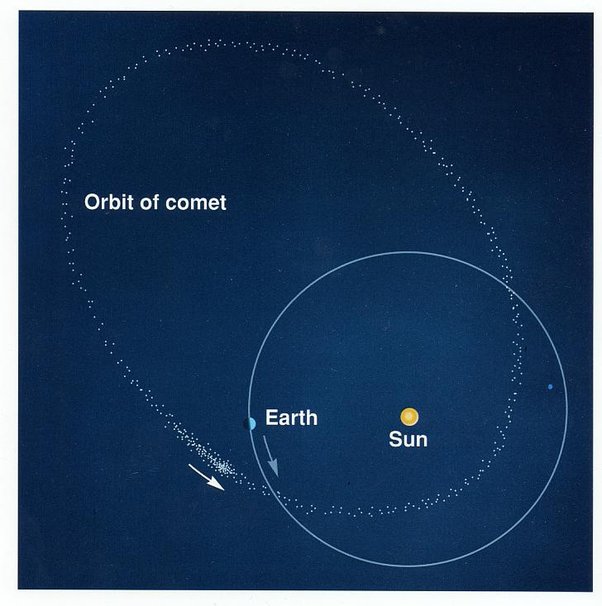

- The Perseid dust grains come from debris by Comet Swift-Tuttle.

- Meteors can travel more than 40 miles per second!

- The Leonids in 1833 were stunning; an estimated 20 meteors per second fell. One witness said, “It was as difficult to count them as to number the raindrops.”

- Most burn up at the top of the Earth’s atmosphere—50 to 70 miles above you!

- The word meteor comes from the Greeks, meaning “high in the air.”

- If the meteor is about bowling ball size, part of it may survive the friction with our atmosphere and impact the Earth as a meteorite.

- Around 1,000 tons of meteorite dust fall to Earth each day!

Blue Moon

Besides an ice cream flavor and a beer, the Blue Moon is the second full moon in the same month. It does not turn blue.

The phrase “once in a Blue Moon” refers to something that is rare in occurrence; so how often do Blue Moons occur? Usually, a little less than three years. We have one this month on August 30. The last one shined back on October 31, 2020. The next one after this year’s is May 31, 2026. Most years, we have 12 full moons. Then, every seven out of 19 years or so, we have 13 full moons. This is because the sun and moon do not dance in perfect harmony. The lunar cycle is 29.53 days. The solar cycle is 365.25 days. These two numbers do not match in any smooth regularity.

The phrase “once in a Blue Moon” refers to something that is rare in occurrence; so how often do Blue Moons occur? Usually, a little less than three years. We have one this month on August 30. The last one shined back on October 31, 2020. The next one after this year’s is May 31, 2026. Most years, we have 12 full moons. Then, every seven out of 19 years or so, we have 13 full moons. This is because the sun and moon do not dance in perfect harmony. The lunar cycle is 29.53 days. The solar cycle is 365.25 days. These two numbers do not match in any smooth regularity.

Sometimes, we can get two Blue Moons in just three months! In 2018, there was a Blue Moon in both January and March. This happens because of quirky February having only 28 days and the lunar phases repeating every 29.53 days. The next time these two Blue Moons occur is January and March 2037. There have been reports that the moon did turn blue due to an extraordinary amount of atmospheric dust particles from volcanic eruptions in 1883 and 1950 – but that is considered extremely rare!

When the Blue Moon expression was first coined hundreds of years ago, it was a metaphor for something absurd or impossible. Somehow, it got translated to having an extra full moon during the year.

In 1946, an amateur astronomer named James Pruett published an article that inadvertently turned the Blue Moon expression into a household name. Misinterpreting the Farmer’s Almanac, he called the second full moon in the same month a Blue Moon. The Almanac had it as the third full moon in a season that regularly has four full moons.

A Blue Moon can turn to gold, too! Well, only if you’re listening to the song "Blue Moon," in which a lonely stargazer finds someone to love. This song, written back in 1934, has been recorded by countless singers, including Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, The Marcels, and Bob Dylan.

A Blue Moon can turn to gold, too! Well, only if you’re listening to the song "Blue Moon," in which a lonely stargazer finds someone to love. This song, written back in 1934, has been recorded by countless singers, including Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, The Marcels, and Bob Dylan.

Far Stars

Estimates say an average person walks 75,000 miles in their entire life. That number equals walking three times around the Earth, or one-third the distance to the moon. That’s a lot of miles! But it’s only 0.0000000125 of a light year. A light year is how far light can travel in one year. At 186,000 miles per second, light travels almost six trillion miles in a year.

The closest star to our sun is 4.2 light years away, or about 25 trillion miles. How do we even measure such a huge distance? The answer goes back to one of your high school math courses, in which you learned trigonometry.

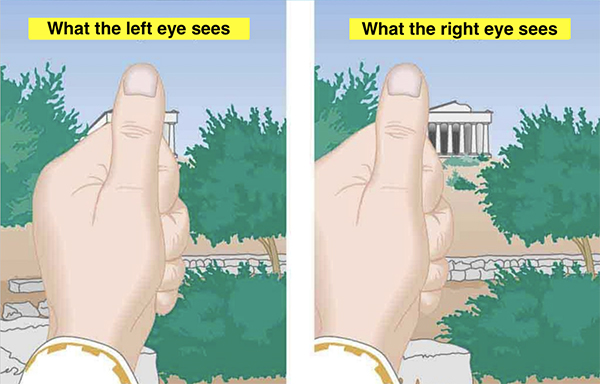

Star distances can be measured using parallax. You may have heard of or done this. Let’s try it now!

Place your right arm straight out in front of you with your thumb up. Next, cover your left eye with your left hand. Notice where your thumb is compared to the more distant background. Now cover your right eye with your left hand. Did you see your thumb jump? Did it really move? Nope! Your thumb appears to move against the background because you are looking at it from two different places—your right eye and your left eye. By measuring the tiny distance between your eyes and the small angle from your eye to your thumb, you can find the distance to your thumb. That’s trigonometry!

Obviously, we can’t use our two eyes to measure stellar distances, but we can use the Earth’s orbit. Astronomers record a star’s position at two different points in the Earth’s orbit, usually six months apart like December and June. If the star moves its position compared to the background stars, they record that small angle. They then measure the distance between the two Earth positions, usually about 186,000,000 miles. Then, voila! They use trigonometry to calculate the star’s distance.

Limitations exist when doing stellar parallax. When stars get very far away, results grow less accurate because measuring the tiny change in the star’s position is very difficult, even with today’s technology. Parallax works best only for the 200 nearest stars — about 300 light years away. Additionally, the increasing amount of light pollution in cities and surrounding areas makes this method difficult to use.

In the past few decades, scientists sent up telescopes around Earth’s orbit to more accurately measure stellar distances using parallax. Two of the telescopes are Hipparcos and Gaia. They have been able to chart the distances of more than one billion stars in our galaxy.

Going farther out, beyond our Milky Way galaxy, astronomers find mammoth distances by using different methods than parallax. One came from Edwin Hubble about 100 years ago. Using the 100-inch telescope on Mount Wilson in California, Hubble discovered distances to galaxies by measuring their redshift, or how much their light is being stretched out by the cosmic expansion of the big bang. Hubble found a linear relationship: The more a galaxy’s redshift, the more distant it is from Earth. Another cosmic measuring tool is variable stars and supernovae. We will take a closer look at those methods next month.

Space in Sixty Seconds

Explore shooting stars, a Blue Moon, and more in the August night sky.

Sky Sights

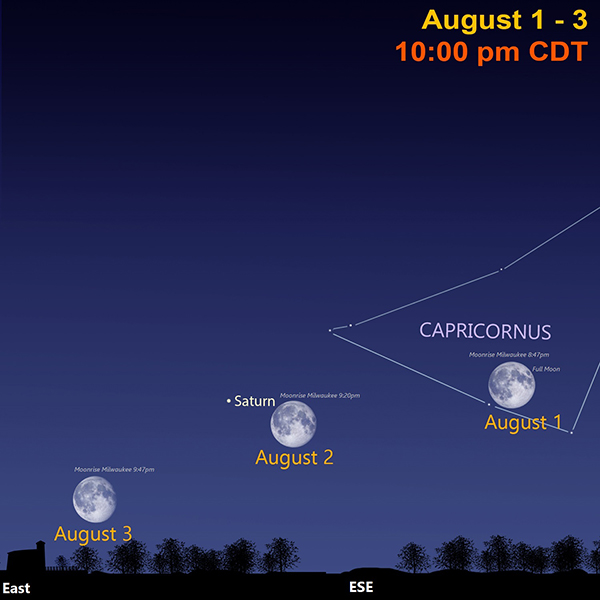

Catch August’s first full Moon on August 1. On August 2, watch our closest space neighbor pair up with Saturn. On August 29-30, watch these two line up again in the ESE sky after sunset. The ring planet is at opposition (opposite the sun) on August 26 when it will rise as the sun sets and sets when the sun rises.

Jupiter and the Moon shine together on the mornings of August 8-9.

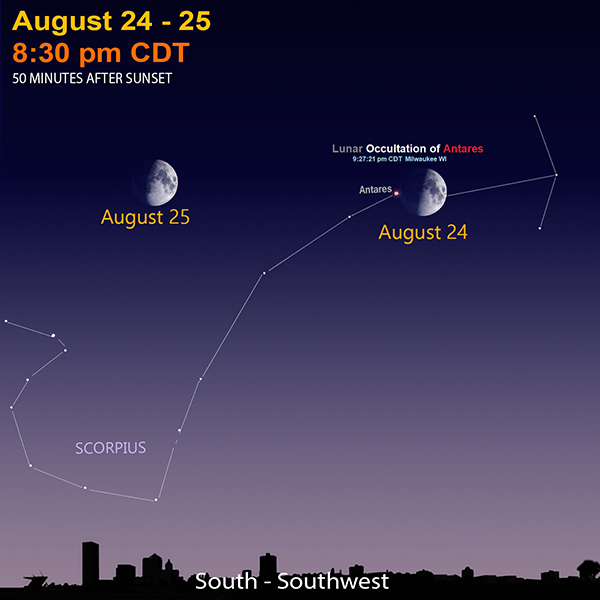

On August 24, a waxing gibbous Moon will eclipse the bright red star Antares in Scorpius. This is called a lunar occultation. These are fun to watch! But be careful, they happen in the blink of an eye. Have an accurate clock handy. Here in Milwaukee, the star Antares will disappear at 9:27:21 p.m. CDT. Times will vary depending on where you live. For an expanded list of locations and times, visit the Lunar Occultations website.

Antares means “heart of the scorpion” in Arabic and Latin languages. In Greek, Antares is the rival of Ares, or Mars.

Venus moves into the morning sky this August. It will be visible more toward the end of the month. What morning will you first see the brightest planet?

Mercury and Mars are very low in the evening sky. You will need binoculars to see them.

August Star Map

Sign Up

Receive this newsletter via email!

Subscribe

See the Universe through a telescope

Join one of the Milwaukee-area astronomy clubs and spot craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the moons of Jupiter, and much more.

Follow Bob on social media

Twitter: @MPMPlanetarium

Facebook: Daniel M. Soref Planetarium