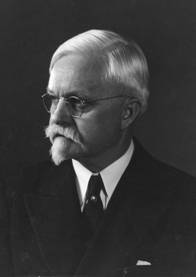

That the MPM endures as one of the finest institutions of its kind in the world is due in no small part to efforts of the Museum’s first Curator of Anthropology, Samuel A. Barrett (1879-1965). Barrett, born in Conway, Alaska, was a student of University of California anthropologist Alfred Kroeber and the first person to receive a PhD in anthropology west of the Mississippi (Lurie 1983: 48). During the course of his education Barrett also studied with the “father” of American anthropology and Northwest Coast ethnography, Franz Boas (for more on Boas, see the section entitled “Kwakiutl Ethnography”), establishing a familiarity with the anthropologist that would serve Barrett well as curator for the MPM in the years to come. Barrett became the first Curator of Anthropology in 1909 and served as the director of the Museum from 1921-1939. During his tenure, Barrett conducted research and collected artifacts for the Museum from British Columbia to Arizona and from the Great Basin to Wisconsin, and saw the museum safely through good times and bad- from the “Gilded Age” to the New Deal and beyond.

Samuel Alfred Barrett (ca. 1910) Source: University of California Berkeley |

Samuel A. Barrett (ca. 1940) Source: Milwaukee Public Museum |

The breadth of Barrett’s experience and expertise astonishes, particularly by contemporary museum standards, which tend to emphasize ethnographic or regional specialization as opposed to the sort of generalization more common in Barrett’s day. When Samuel Barrett decided that the MPM needed to establish a Northwest Coast Indian collection he turned to his former teacher Franz Boas for advice. Boas immediately put him in touch with his close associate, Pacific coast native George Hunt (for more on George Hunt, see the section entitled “Kwakiutl Ethnography”). Hunt corresponded with Barrett over a period of several months, eventually renting out a house on Vancouver Island to Barrett and offering him advice on where, when, and how to best collect Kwakiutl materials. In January of 1915, Barrett arrived at Fort Rupert, British Columbia, and Hunt joined him as a guide and translator (Cole 1985: 248).

One of Barrett’s objectives was to modernize the MPM, which, at the time, consisted of exhibit rooms full of glass cases cluttered with artifacts and little or no explanation of what those cases contained. Further, Barrett seemed to be aware of a public interest in what was then the very young science of anthropology and wanted to deliver to museum goers what he perceived to be an “authentic” ethnographic experience (Stolte 2009: 36, 40). Along with MPM artist George Peter, Barrett consulted with local people to create life-sized dioramas, hoping to achieve the highest degree of accuracy in his depiction of Kwakiutl life before the widespread arrival of European settlers. Though some of these dioramas have undergone renovation since they were installed, the MPM still houses most of these early life group displays.

Barrett’s Northwest Coast Diorama at the Milwaukee Public Museum

Barrett published several manuscripts and scholarly reviews on ethnography and archaeology while serving at the MPM, and worked actively with Native American groups and at archaeological sites throughout the U.S. Indeed, in 1924 President Calvin Coolidge established the Wupatki National Monument to preserve the prehistoric pueblos found at the site, in large part due to the efforts of Barrett and fellow anthropologist Harold S. Colton. Barrett was also one of the first anthropologists to recognize the value of film as a tool for cultural documentation (Snyder 1967: 428). Following his tenure at the Milwaukee Public Museum, Barrett returned to the University of California where he and his mentor, Alfred Kroeber, created a series of over twenty documentaries about the indigenous peoples of the western United States.

Certainly, Samuel Barrett was not without his shortcomings. Field notes for the objects Barrett collected are often incomplete; names of the craftspeople and families who sold Barrett their possessions or crafts are largely missing, as are detailed ethnographic accounts of his collecting. Similarly, though Barrett consulted local people for ethnographic details, the resulting dioramas and ethnographic representations cannot entirely be considered collaborative efforts, as Barrett was subject to -and an agent of- the prevailing prejudices and power dynamics of his time (Gentilli 1999; Stolte 2009: 71-72). Despite these issues, however, Barrett’s devotion to the MPM and his efforts to increase the museum’s collections and develop its exhibitions warrant acclaim, and have earned the institution its grand reputation as a first class museum among researchers, its many visitors, and the public that calls Milwaukee their home.