Like most Arctic and Subarctic culture complexes, Sami spirituality was traditionally natural and shamanic.

The forces of nature were the deities and spirits that ruled every important aspect of nature, and of Sami lives. Animals, plants, and even inanimate objects had a soul. Offerings and sacrifices were made at holy natural or human-built sites in the land. Through a type of singsong chant called the joik, Sami conveyed legends and expressed their spirituality (McLeod, 2006).

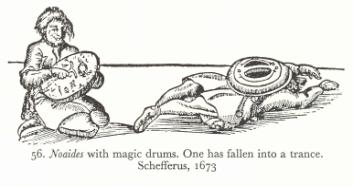

The drum was a crucial part of Sami shamanism as it facilitated transcendence between the human world and the spirit world. Though every household had a drum, only a few individuals possessed real power. These were called the noiades, or shamans. The drum was used to induce ecstasies, and it was during these trance states that the noiade was able to wander into the spirit world and achieve great things with those sacred animals that served as his assistant spirits (Vorren and Manker 2006: 123). Drums were most commonly used for the purposes of foretelling weather and other conditions for herding travel.

Christianity was introduced to the Sami with the influx of Scandinavians, many of whom believed the Sami were a backward race and regarded their shamanic practice as devil worship. Throughout the region, laws were created to deny the Sami rights to their land and to the practice of traditional livelihoods.

At the end of the 17th century, through royal decree, a church was built especially for the Sami in Varanger, Norway. Sami who then attempted to practice their traditional religion were persecuted-–some even burned at the stake for "witchcraft"–-and holy sites and drums were destroyed. However, several drums still exist in museums and private households today. Despite initial rebellion against Christianity, in time the Sami became loyal worshippers. In the form of Christianity that most Sami adopted, the feeling of the shamanic ecstasy was echoed in the emotion-charged excitement that could build up during gatherings (Ibid, 130). One man in particular, Lars Levi Laestadius (1800-1861), was instrumental in spreading Lutheranism among the Sami. Being half Sami himself, and with an apparent penchant for learning languages, Laestadius was eventually able to give sermons in Finnish and Swedish as well as several Sami dialects (Hepokoski 1993).

Because the nomadic lifestyle and the immensity of the Sami landscape prohibited frequent and regular masses, church-going began to occur on annual migrations and at certain special times of year during festivals and markets. It was during these occasions that traditional Sami dress was–and still is–worn as a celebration of Sami culture. Though most fastboende do not wear this tracht dress on a regular basis, some flytte still do.

Vorren and Manker 1962, page 122

Photos of a Sami Lutheran wedding

Photo credit: Fred Ivar Utsi Klemetsen

"Frost" exhibit, Smithsonian Institution, 2006